On Bangladesh Accord’s anniversary, brands should commit to new binding safety agreement to safeguard its work

On 15 May 2013, only weeks after the Rana Plaza collapse killed at least 1,134 people, brands and retailers signed the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh with unions. This groundbreaking legally-binding agreement is expiring on 31 May, two weeks from now, just after the eighth anniversary of its programme that has made 1,600 factories safer for over two million garment workers.

Unions and labour rights organisations urge the 200 brands and retailers that are current signatories of the Accord to sign a new legally binding safety agreement to meet supply chain due diligence obligations that will soon be mandatory on all brands operating in the EU by safeguarding the progress made by the Accord and expanding it to other countries.

While there is a clear international trend towards introducing mandatory supply chain legislation in a range of EU member states and at the EU level, apparel brands and retailers are moving in the opposite direction by allowing the Bangladesh Accord agreement to run out. A comprehensive study from 2020 on the current implementation of due diligence in supply chains of European business enterprises, commissioned by the European Committee, praised the Accord for meeting the requirements of due diligence for its binding nature, inclusiveness, and enforceability. At a moment when there is growing awareness among policy-makers and even among many brands and retailers that voluntary mechanisms are failing to bring accountability and meaningful change for workers, most of those same brands are now standing by idly and letting the one binding agreement that already is keeping workers safe in their supply chains expire.

Brands and retailers whose due diligence obligations on factory safety are now covered by a credible mechanism that could, under a global agreement, be expanded to include their supplier factories in other countries, are wilfully leaving that programme behind, even though they know that they still have life-threatening human rights risks in their supply chains. A recent report by the Accord witness signatories shows that major brands, such as H&M, C&A, and Bestseller, still have dozens of supplier factories where tens of thousands of workers risk not being able to exit a factory safely or not be alerted to a fire due to a lack of safe exit routes or verified fire alarms. The importance of having an independent mechanism to verify the satisfactory completion of required remediations is illustrated by the fact that almost 25% of renovations (p. 15) that are reported as completed turn out to be not up to standard when verified by independent engineers. One can only imagine what this would mean if vital human rights due diligence obligations like ensuring a safe workplace are left to brands, retailers, and factory owners alone.

Brands and retailers however continue to be set on a course away from the current enforceable standards. Instead of signing a new binding agreement, many brands indicated they want to rely solely on the RMG Sustainability Council that took up the Accord’s on the ground operations, but that cannot hold brands to account. Without the backup of a legally binding and enforceable agreement through which unions can hold individual brands and retailers accountable, such a mechanism would be no better than the kind of voluntary programmes that failed to prevent the collapse of Rana Plaza and the death of hundreds of garment workers in dozens of other incidents. This is precisely why in January 2020, the brand and union signatories to the Accord agreed to create a new global agreement to embed the RSC's work in legal enforceability upon brands. Brands are now backtracking on that commitment.

The Bangladeshi and global unions that now hold one third of the seats in the RSC have announced they will withdraw participation on 1 June if a binding agreement is not reached, meaning that the RSC will become a mere exercise in brand and factory self-monitoring without worker participation, independent oversight, or accountability. One wonders why, in the light of mandatory due diligence legislation under consideration at the EU level and in a range of European countries, brands would let go of the one programme that is already addressing a significant category of risks in their supply chain.

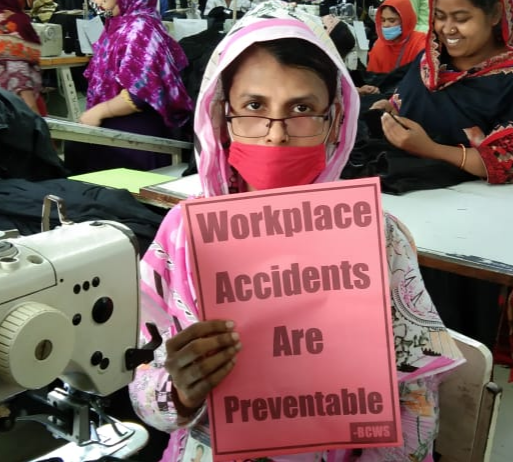

Kalpona Akter, president of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation and founder of the Bangladesh Centre for Worker Solidarity said: “Brands and retailers must make sure that an incident like Rana Plaza can not happen again, here in Bangladesh, or in any other production country. Our workers’ lives are important. These are the workers who have enabled profit for the manufacturers and brands and retailers for years. Those who reap the profits have a responsibility, soon even by law, to make our workplaces safe." Akter added: "If we had had the Accord before, we could have saved all those lives that were lost in the Rana Plaza collapse.”

Agnes Jongerius, a Member of European Parliament for the Netherlands (S&D), said: “Eight years ago the Accord was established for good reasons, to protect workers against dangerous working conditions and to put their safety first. Especially in these uncertain times during a pandemic it's extremely irresponsible for brands to backtrack on the one agreement that is holding brands accountable to their promise to keep workers safe in the workplace.”

Ineke Zeldenrust of Clean Clothes Campaign says: “Brands are proposing a type of agreement that we know from before 2012 -- one that is no longer legally binding upon individual brands and has no independent secretariat to oversee brand compliance. Under the guise of setting up a lean structure brands are in fact returning to self-monitoring, in direct contradiction of what upcoming legislation is demanding.”

Find out more.