Two Bangladeshi tragedies: why have some brands still not learned their lesson?

Two tragedies in the Bangladeshi garment and textile industry last month have brought back attention to the issue of safety of Bangladeshi garment workers. Massive improvements in the wake of the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013 have ensured that most garment workers sewing clothes for international brands no longer have to fear their lives at work. Yet workers in factories not covered by the International Accord on Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry responsible for these improvements, remain at risk.

Two tragedies

This became painfully apparent in the past weeks. On 14 October, a five-story building that housed two printing factories and at least one active garment factory in the Dhaka area Mirpur burnt down when a neighbouring chemical warehouse caught fire. The workers were trapped inside without any means to exit. The death toll stands at 17.

Less than two weeks later, on 26 October, at least six workers sustained severe burn injuries following an explosion in a room reportedly holding the gas meter of two adjoining garment factories, M.S. Dyeing, Printing and Finishing Limited, and Fair Apparels limited, in the Dhaka Fatullah area.

The factories in the Mirpur area building are hard to link to international brands’ supply chains, but the Fatullah factories do have connections to international brands. Trade data link M.S. Dyeing, Printing and Finishing Ltd to Gor Factory (Spain), New Yorker (Germany), Fox Wizel Bvi Limited (Malaysia), Storm Textil (Denmark), Camac Arti and Sei Due Sei (Italy) and Solo Invest (France). Fair Apparels Ltd buyers include Brandbq (Poland), Unibrands (Sweden), Socim (Italy), Hipermercados Tottus (Peru), Willy Maisel (Germany), Piazza Italia (Italy), Rip Curl (USA/Australia), Lager 157 (Sweden), Terstal Textiel (Netherlands), Toads (France), and Sabor Srl (Italy).

Brands should be held accountable

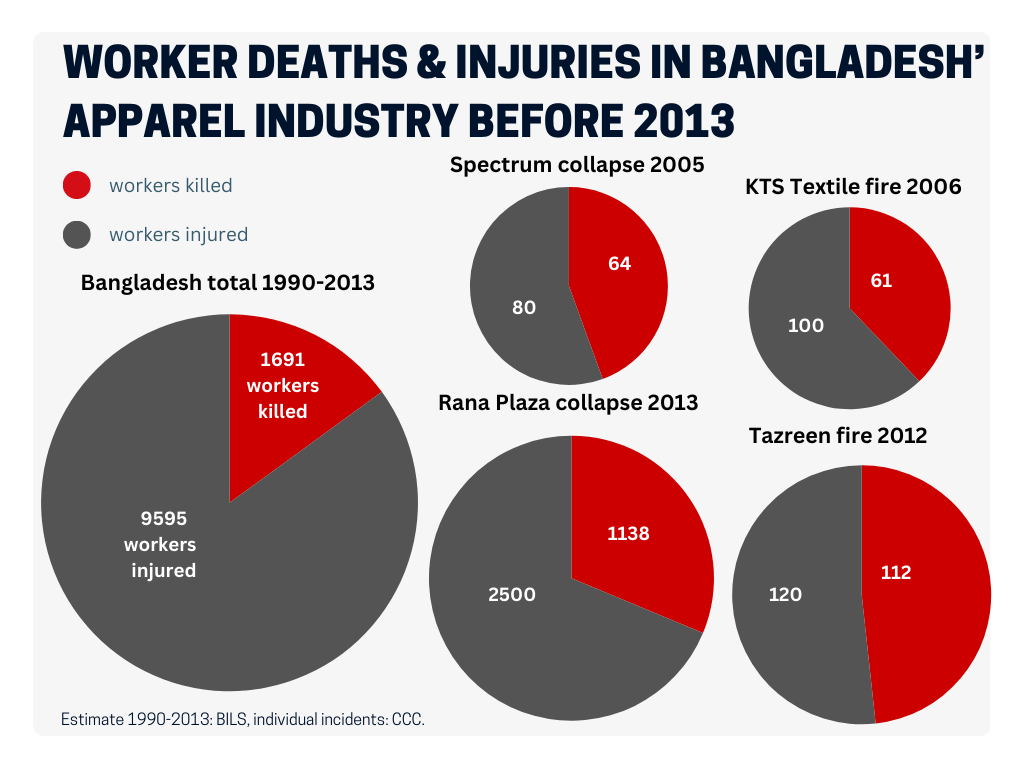

Brands have a responsibility under the UN Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights to protect their workers from deadly hazards. The era of disasters in the Bangladeshi garment industry, between 2005 and 2013 must have imprinted garment brands around the world with the realisation that garment workers in Bangladesh often risk their lives at work. Several of the Fatullah blast brands have first hand experience: New Yorker was linked to at least two major factory incidents with a combined death toll of 85 and over 120 deaths (Spectrum collapse of 2005 and Garib & Garib fire of 2010). Piazza Italia was linked to the 2012 Tazreen fire, in which 113 workers lost their lives and nearly 200 were injured. Both were linked to a factory where a union leader was beaten to death two years ago, as was Lager 157. All these brands should be amply aware of the importance of keeping workers in their supply chain safe. Yet these brands deliberately chose to ignore the International Accord and risk their workers’ lives.

One of the factories involved in the Fatullah explosion, M.S. Dyeing, Printing and Finishing, was even publicly listed by the Accord as unsafe. It was covered by the Accord programme until 2018 and then entered the final stage of the programme’s escalation process for repeatedly failing to address life-threatening safety risks. If a factory reaches this stage, all signatory companies have to terminate their business relationship with the factory, the factory is placed on a publicly available list of unsafe factories, and workers are notified. Clearly, the brands sourcing from this factory not only decided against signing the one programme that keeps workers safe, they also chose to place orders without minimal due diligence being done.

The latter, unfortunately, also seems to be the case for one Accord brand. While Accord brands are prohibited from sourcing from factories on this ineligible factories list, Solo Invest was sourcing from this ineligible factory. Additionally to not checking the list before placing orders, Solo Invest clearly also failed to inform the Accord immediately of this new sourcing relation. If it would have done so, the Accord would immediately have reminded the company that this factory was out of bounds. Additionally, another Accord signatory, Sabor Srl, received at least one shipment from the other Fatullah factory, Fair Apparels. While Fair Apparels is not an ineligible factory, Sabor clearly broke the rule that it should let the Accord know where it sources, as the factory is not listed on the Accord website. The Accord should ensure these brands are held accountable for breaking the agreement’s terms.

Government action is needed to step up

The Department of Inspection for Factories and Establishments (DIFE) and the Industrial Safety Unit (ISU) are the entities responsible for factory safety in Bangladeshi factories where the Accord does not have a mandate. They did not ensure that these factories were up to standard, even though in the case of M.S. Dyeing, Printing and Knitting they were officially notified by the Accord that this factory had escalated out of its programme. The operating licence of the factory was not withdrawn, and it was allowed to continue to export. The employer organisation Bangladesh Garment Manufacturer and Exporter Association (BGMEA), to which the Fatullah factories belong, continued to issue the factory the so-called “Utility Declarations” (UD), a necessary declaration required to export each order. It’s time to ensure that all workers in Bangladeshi factories are kept equally safe.

Time for action

CCC calls upon:

all the brands that have not yet done so to sign the Accord, especially the brands sourcing from the factories involved in these incidents.

the Accord to enhance its monitoring and enforcement of signatory obligations not to source from ineligible factories and hold brands that violate their obligations to account.

the interim government of Bangladesh and the Accord to ensure that factories are equally safe whether they have been inspected by Accord/RSC or DIFE/ISU, through shared standard-setting and exchange of technical expertise; and to ensure shared monitoring mechanisms for factories that are found to be ineligible.

the interim government of Bangladesh to bring UD issuance and withdrawal under the purview of the government instead of employers and cancel licences to operate for factories that are made ineligible and fail to address their compliance-related issues.

all parties involved to ensure full compensation for all victims and their families. The workers are eligible for compensation for loss of income and medical costs under the Employment Injury Scheme pilot, but this links to the current poverty wages in the industry. Therefore, additional compensation for pain and suffering, in line with among others the 2016 Appellate Division judgment of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh, is needed in order not to leave families in abject poverty.