Bangladesh government proposes new poverty wage of 12,500 BDT ($113) per month, ignoring the workers’ desperate calls

Bangladesh’s labour ministry proposed a new minimum wage for the country’s 4.4 million garment workers at 12,500 BDT (113 USD) on Tuesday 7 November. The amount is far below the trade union demand of 23,000 BDT, a wage that research studies confirm is the minimum required to place workers above the poverty line.

The new minimum wage condemns workers to a struggle for basic survival for the next 5 years. Workers are already relying on income earned in extra shifts (on top of their normal 48-hour work week), loans and skipping meals to save money. Poverty wages are also the main reason why parents sometimes find themselves forced to ask their children to work.

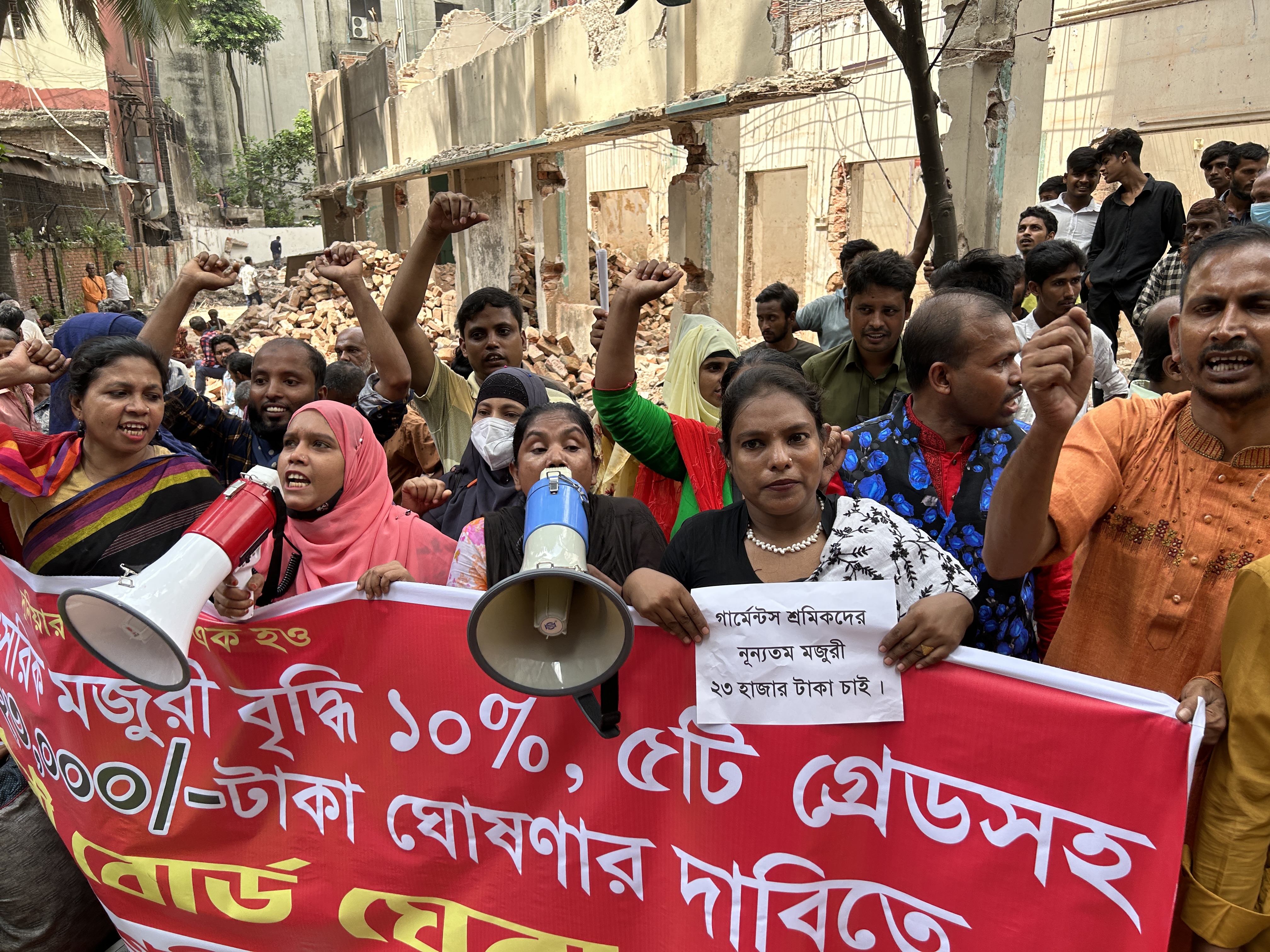

The highly untransparent and biased wage-setting process was finalised after weeks of unrest in Bangladesh. Workers around the country started protesting after the BGMEA had proposed to raise the Minimum Wage to a meagre 10,400 BDT last month. At least 3 workers have been killed during the protests, with dozens of workers injured after facing police violence in the form of tear gas, rubber bullets and live ammunition. Cases are being filed against protesting workers raising serious concerns for retaliatory arrests. Yesterday’s announcement might spark further unrest in the Bangladeshi capital.

Factory owners in Bangladesh claim they cannot afford the minimum wage to be set higher than 12,500 BDT, and some claim this wage might even put some subcontractors out of business. However, it is the buyers – the international fashion brands – who dictate prices in the industry. In principle, their purchasing prices should always allow factory owners to pay workers a living wage. Still, in most cases, the prices paid by brands are barely enough to pay the poverty-level minimum wages in countries like Bangladesh.

Despite multiple calls by CCC for international buyers to explicitly back the trade union demand for a 23,000 BDT minimum wage, and to assure suppliers that they would raise their own prices in accordance with the labour cost increase, all but one brand refused to do so.*

Many brands sourcing from Bangladesh, including H&M, Next, C&A, Uniqlo and M&S have long-standing living wage commitments. Yet at the most crucial moment for the brands to use their outsized leverage to assure their own workers are not living in poverty, they have failed to act, illustrating the emptiness of these commitments to living wages.

The Prime Minister has yet to implement the new wage. It is now up to these brands to put their money where their mouth is and ensure workers in their supply chain earn at least 23,000 BDT, which is still not a living wage but the bare minimum that is needed for workers to make ends meet.

Trade unions in Bangladesh have raised sharp criticism of the integrity of the wage-setting process, just like five years ago. Trade unions demand annual revisions of the minimum wage, instead of once every five years. Trade unions also point out that the workers’ representative on the Wage Board must be selected from the most representative trade union. In this and previous wage negotiations, this regulation has been flouted to install a “workers’ representative” who is favourable to employer and government interests.

Finally, trade union leaders point out that their proposal for 23,000 BDT was reached using criteria prescribed under both the country’s labour law (the Bangladesh Labor Act) and international labour standards (ILO Convention 131 on Minimum Wage Fixing), while the employers’ proposal was not.

* Patagonia was the only brand explicitly supporting the trade union demand for 23,000 Taka but it did not commit to increasing the prices it would pay to its supplier. Other brands vaguely supported demands for higher wages, but refused to explicitly back the trade union demand for 23,000 BDT or commit to increasing prices.