The devastation of COVID-19 on UNIQLO's former garment workers

During the current COVID-19 crisis, those who are the most vulnerable must be tended to first, and multi-national clothing brands should not be allowed to ignore their responsibilities. Uniqlo must take urgent action to help the 2,000 workers of Jaba Garmindo who have no income and whose only hope is retrieving the $5.5 million they are legally-owed in severance pay.

COVID-19 is brutal, indiscriminate in who it touches, however we are not all facing the same risks. Money can buy some protection and it provides choices, even as the options narrow. Garment workers, the vast majority of whom are women, have very few choices in this crisis. COVID-19 has held the immorality of global capitalism to the light, exposing its innate inequalities. The garment industry is one where the power has always been held by clothing brands who use it to drive down prices, chasing lower labour costs and faster turnaround times, swapping factories or producing countries at will, looking for those with the laxest labour laws and the most compliant/fearful workforce. It is these purchasing practices that fuel labour abuses as factory owners cut corners on safety and garment workers are paid wages that barely cover their essentials, trapped in a cycle of poverty. None of this is new, but recent events have shone a spotlight on how deep the power imbalance goes, and how, even in times of global emergency the likes of which we’ve never seen before, shareholders profits continue to come above garment workers lives.

In Bangladesh, workers have been on the streets protesting for unpaid wages after brands including Primark, Asos, Gap and Urban Outfitters refuse to pay for orders in full, leaving the industry in chaos and workers, once again, shouldering the burden. 80% of Bangladesh’s export trade is clothing, and approximately $3 billion worth of orders have not been paid for since this crisis began. Garment workers fear the very real threat of starvation as much as they fear infection, and the Clean Clothes Campaign, alongside other workers’ rights organisations, are holding brands to account for their blatant disregard for human life. Factories across the global south are re-opening amid concerns for workers’ safety, where crowded conditions are the norm, including dangerously full transport trucks taking workers to and from factories, and few safety measures in place. Garment workers are unable to refuse because their monthly wages do not stretch to savings, they have nothing to tide them over if they don’t work. COVID-19 may have compounded their grim situation, bringing the inequalities of the garment industry to the fore, but it did not create them.

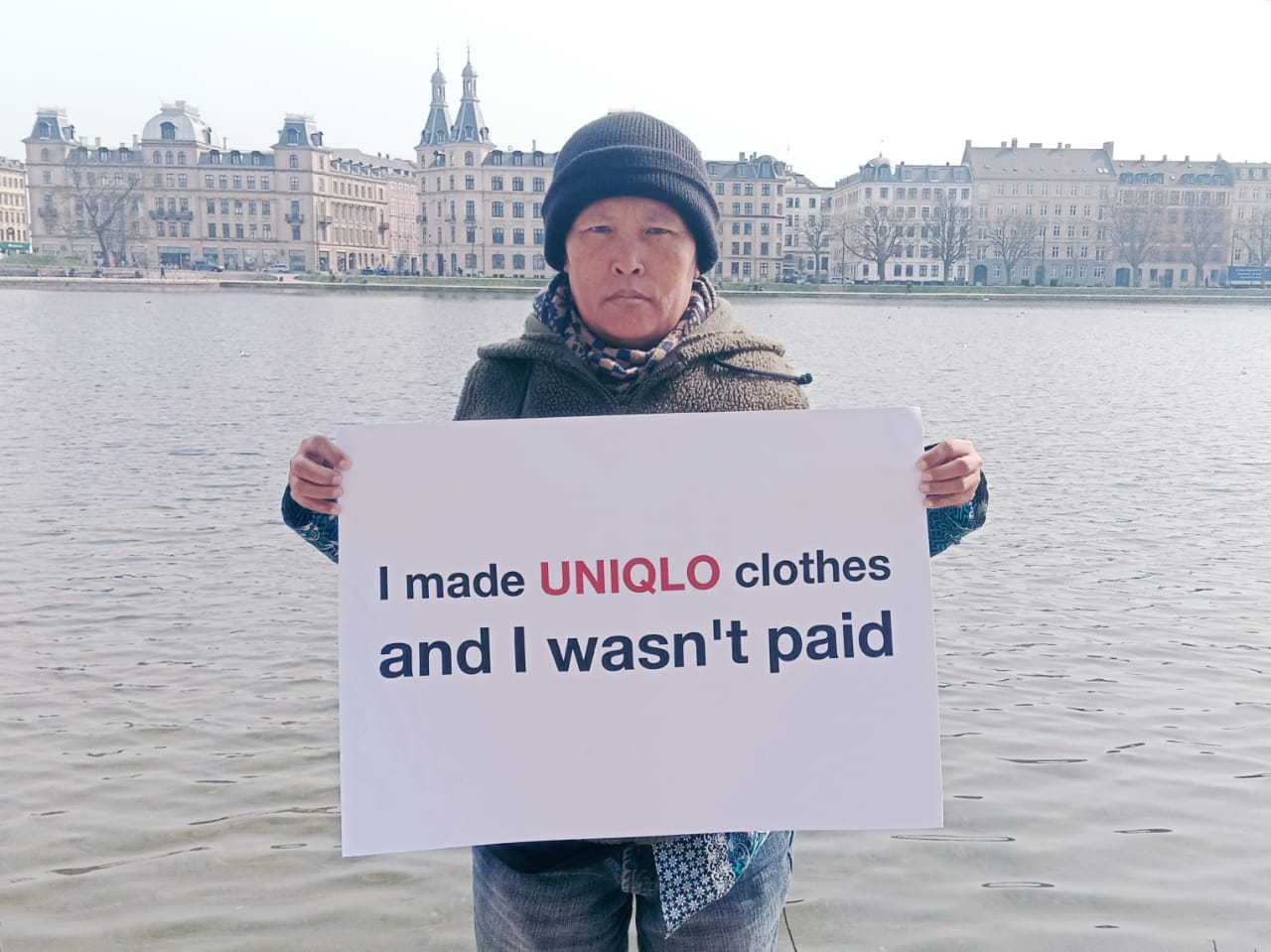

Some of the worst hit economically by this pandemic are informal workers whose entire business has been decimated by COVID-19 restrictions, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 1.6 billion workers in the informal economy face “massive damage” to their livelihood. In this crisis, those who are the most vulnerable must be tended to first, and multi-national clothing brands should not be allowed to ignore their responsibilities. Uniqlo is one such brand. Five years ago this April, the Jaba Garmindo factory, which made clothes for Uniqlo, went bankrupt in Indonesia; in one of the worst and unresolved cases of severance wage theft ever, 2,000 garment workers have been fighting for $5.5 million legally-owed to them in severance pay. The workers, mostly women, struggled to find new factory work following the bankruptcy, often discriminated against for being too old, having worked at Jaba Garmindo for years, or unofficially blacklisted due to their ongoing campaigning efforts. For a great many the only work available has been informal: cleaning clams for fishermen, washing clothes for neighbours, childcare, street vending – all jobs that are banned under current COVID-19 movement restrictions. These workers have no safety net beneath them, no state benefits available and they do not qualify for any COVID-19 related financial relief. With no income at all they are truly desperate, with one worker stating: “We only eat plain rice, it’s all we can afford and even that is bought on borrowed money. I don’t know what will happen if things continue like this.” Their only hope is to be paid the $5.5 million they are owed by law. Many of the workers have already been forced to borrow from loan sharks simply to survive this long. They are fast running out of options, and soon even plain rice will be beyond them.

International standards dictate that companies must address and remedy the adverse human rights impacts of their business practices and, had Uniqlo acted responsibly in its exit from the factory, the 2,000 Jaba Garmindo workers would not be in such profoundly vulnerable positions now. $5.5 million is inconsequential to a brand worth $8.6 billion. Tadashi Yanai, the CEO of Fast Retailing, parent company of Uniqlo, is the richest man in Japan. He has a net worth of $31.4 billion, a fortune built from the sweat and hard work of garment workers, and yet the lives of 2,000 workers hang in the balance and Uniqlo is taking no steps to remedy this. In its drive for greater profits, it is even continuing to open new stores during this crisis.

A key issue here is the lack of legislation to protect garment workers and to hold brands to account, and voluntary initiatives stand in where laws should be. These give the appearance of upholding ethical standards, however they have little to no power behind them to truly demand better of brands. Uniqlo, under Fast Retailing, is a member of the Fair Labor Association (FLA), a social compliance initiative aiming to set standards and ensure compliance by assessing the ethical performance of its member brands. The FLA are currently investigating Uniqlo for its failures in the Jaba Garmindo case. Having exhausted all other options, this is the last available avenue for the workers to retrieve the money they are owed. They have already been to court in Indonesia, where their claim to the $5.5 million was upheld, however the court has no power over a multinational brand such as Uniqlo. The workers have attempted mediation with Uniqlo, but the brand did not attend in good faith and has since refused to engage with them. They have protested, told their stories, raised their voices, yet still their money is owing.

The world should watch the FLA’s next steps. To have any legitimacy as a multi-stakeholder initiative aiming to promote and protect workers’ rights, the FLA needs to deal swiftly with this urgent case. It should bypass its usual steps, taking into account the devastating and extraordinary circumstances workers now find themselves in, and be firm in issuing consequences to Uniqlo for failing to uphold ethical standards; if they fail to do so, questions must be asked over what their role and purpose actually is? There are few reliable and effective mechanisms available to workers, and the only thing that will truly protect workers is a firm move towards binding legal agreements with decisive repercussions for brands who break them. No-one should have to rely on voluntary initiatives for the protection of their human rights.

As a brand, Uniqlo has spent millions shaping its public profile. Utilising an intentional PR tactic, it has partnered with organisations including the ILO and UN Women to help cultivate the image of an ethical brand. This is not altruism or philanthropy, this is a cold, hard, money-driven tactic and a cynical use of partnerships to boost its’ ethical credentials. If Uniqlo truly wanted to do good it could start by righting a wrong committed five years ago and paying 2,000 workers the money they are owed. It is no coincidence that, as the Jaba Garmindo campaign has gained international support over the last two years, so has Uniqlo’s attempts to build connections with oragnisations that counter the public narrative. The brand has spent over $3 million on its partnerships with the ILO and UN Women to seemingly address the exact issues that are at the heart of this case, namely promoting decent work for all and combating the exploitation of female garment workers. While this plays well in the media and public consciousness, the brand still refuses to pay the Jaba Garmindo workers what they are owed, even as their prospects grow increasingly dire by the day.

In their global partnership with UN Women, Uniqlo aims to “create an enabling environment for all women in our business” by supporting the “activities of each and every woman who contributes to Uniqlo clothes-making”. However, enabling women must include economic empowerment. UN Women have partnered with a company actively refusing to ensure the economic empowerment of the Jaba Garmindo workers. These women are leaders in their community, campaigning against a multinational brand for five years and continuing to fight for their rights. They are hoping to reinforce an emerging industry standard of brand responsibility in factory closure cases. UN Women, an organisation dedicated to championing women’s equality worldwide, should be supporting and amplifying the voices of the former Jaba Garmindo workers. Instead, it is taking money from a company with a questionable human rights record to establish a programme ostensibly to address female empowerment while ignoring the very same issue in its partner’s supply chain. Far from addressing women’s rights, this case highlights how UN Women are actively reinforcing the global systems and structures that keep women repressed. After all, female empowerment cannot be based upon a corporate definition of what this is or a brand-led decision on who should benefit from it.

COVID-19 is changing the world, and none of us can accurately predict what it will look like in one month’s time or one year from now. Let us hope that one of the differences is a global understanding that exploitative practices should not be a foundation for our collective future, and a realisation that capitalism will not save us. The power balance needs to be redressed, and brands must value the lives of those who make their profits possible. In no case is this more urgent than that of Jaba Garmindo and Uniqlo. #PayUpUniqlo