Survivors of deadly garment factory fire continue to fight for full justice

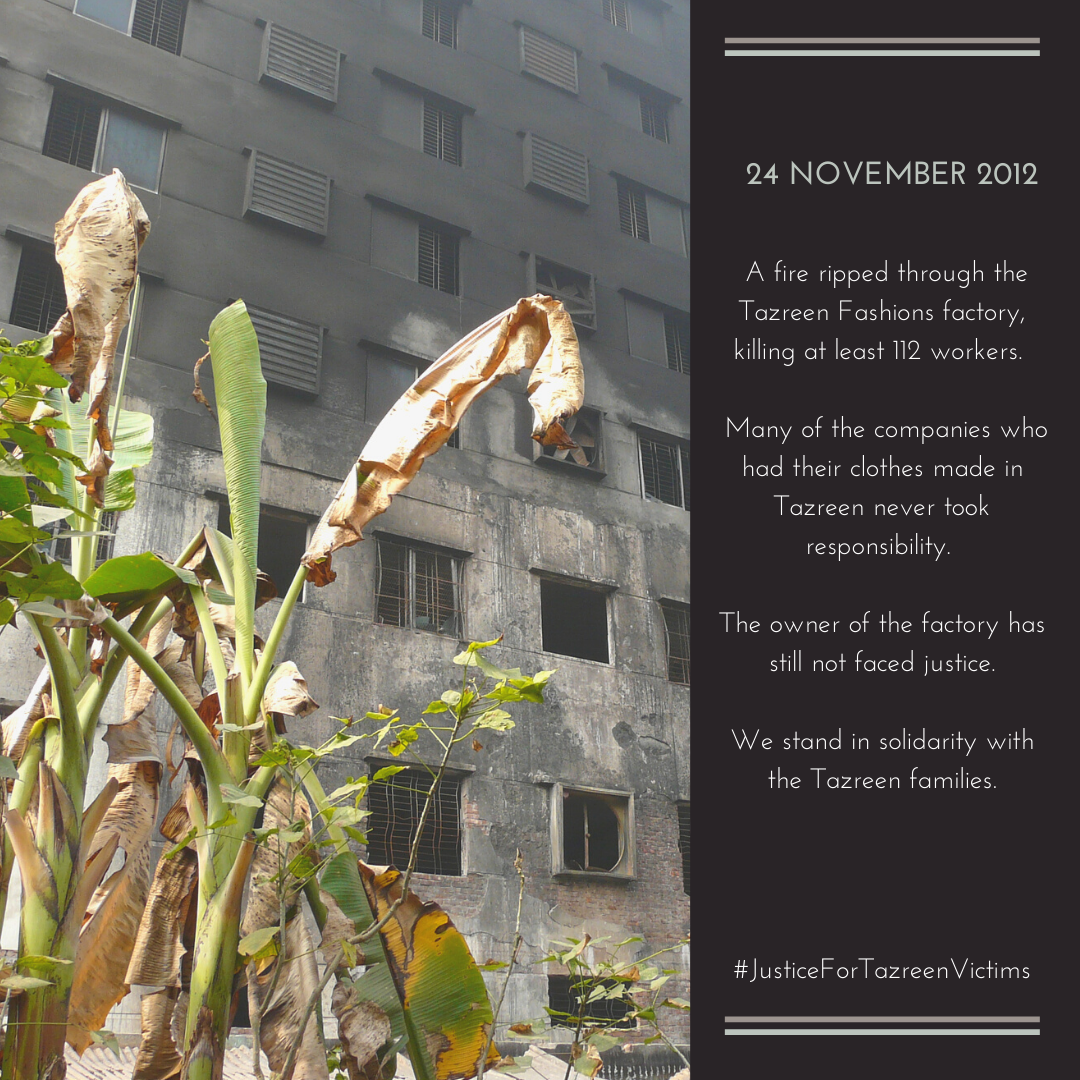

Eight years ago today, a fire in the Tazreen Fashions factory in Bangladesh trapped hundreds of workers in a building without fire exits. At least 112 workers died and many more were injured for life after jumping from upper floors. Despite receiving compensation for medical costs and loss of income per international standards, full justice is still outstanding, and a group of severely injured workers spend their days protesting to ask attention for their destitution.

On this day, our thoughts and solidarity go out to all workers who had to live through this tragedy and all families who lost loved ones that day. We pledge to continue to fight for better social protection, including employment injury insurance, and living wages.

Brands who consciously source from a country with failing social protections have to be willing to carry the responsibility that comes with that. It is widely known that Bangladesh’s compensation system for workers injured or killed at the workplace woefully inadequate. Families of workers deceased on the job receive a lump sum of less than 1,000 euro (100,000 BDT), while a worker injured for life receives only slightly more (1,200 euro/125,000 BDT). That is why, together with the Tazreen families and survivors as well as unions in Bangladesh and globally, we turned to brands and retailers who sourced from the factory. By September 2015, the Tazreen Claims Administration Trust, was set up to oversee calculation and distribution of loss of income payments to the Tazreen families, and we urged brands to contribute financially. Although the calculated amount was indeed reached through company donations, many brands and retailers failed to take any responsibility at all. These included Edinburgh Woollen Mill, Piazza Italia, Disney, Sears, Dickies, Delta Apparel, and Karl Rieker.

The compensation payments under the Tazreen Claims Trust were an important addition to the meagre national payments. The amounts were calculated according to international norms laid down in ILO Convention 121. However, since the convention uses the actual paid wages as the base, the compensation amounts calculated to pay for life-long wage-loss – even if corrected for inflation – come out at painfully low levels. This is caused by the poverty wage level prevalent in the industry. For international norms to be more applicable in a country like Bangladesh, and for worker welfare in general, the minimum wage for garment workers would have to be tripled at least. If a wage system sustains poverty in working people, a social protection system based on maintenance of that particular income is bound to sustain destitution among those incapacitated to work.

Furthermore, Convention 121 only covers compensation for loss of income and does not include compensation for pain and suffering, which falls outside of the ILO framework. In absence of this, full and fair compensation and complete justice is still far off for the Tazreen survivors and families. Even more so because eight years on, the prosecution of Delwar Hossain, the owner of Tazreen Fashions, has still not been concluded. Clean Clothes Campaign calls for full justice for Tazreen families, which would include compensation for pain and suffering and transparent and swift court proceedings.

In 2016, as part of the aftermath of two major factory disasters in the Bangladeshi garment industry, at Tazreen in 2012 and Rana Plaza in 2013, a Trust for Injured Workers’ Medical Care was established. The fund is open for any former Tazreen worker with medical problems, also if the issues developed later in life, and should alleviate some of the financial and physical burdens of the workers. We will be working with our Bangladeshi union and civil society colleagues on the Trust board to explore whether what role the Trust can play in supporting survivors who are currently protesting.

Eight years after the tragedy, we continue to call upon the government of Bangladesh to make haste with the pilot project for an employment injury insurance scheme that it has committed to five years ago. A life-long pension scheme, rather than payment through lump sum (which was the wish of the Tazreen families at the time) would be a long-term contribution to easing the hardship of those who survived work-place incidents, even though without compensation for pain and suffering justice remains incomplete. For loss of income payments to furthermore be a real form of relief, the minimum wage in Bangladesh’s ready-made-garment sector urgently needs to be raised to a living wage level. Bangladesh can and must leave the time behind that injury on the job equals life-long deprivation.