Faulty Pakistan factory audit: Italian social auditor RINA yet again disregards families harmed by textile factory fire

Italian social auditing company RINA Services S.p.A. has refused to take responsibility for the faulty certification of a garment factory in Karachi (Pakistan) in which over 250 people died. Pakistani survivor and labour rights organisations together with European allies had filed a complaint at the Italian OECD National Contact Point in September 2018.

After months of mediation, RINA refused to sign the mediation agreement which would have led to payments to the affected families and obliged the company to improve its auditing practices.

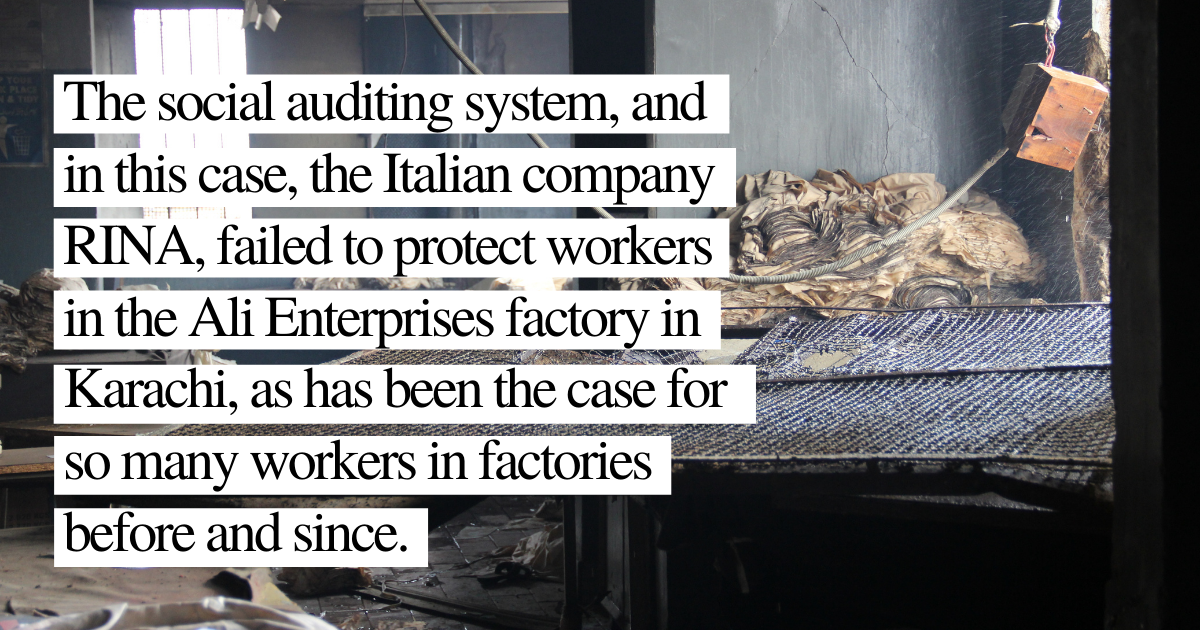

On 11 September 2012, a fire swept through the Ali Enterprises factory in Karachi only three weeks after the factory was certificated by RINA as compliant with the SA8000 norm – an international standard set by Social Accountability International. The auditor had overlooked a range of safety obligations, such as the need to have a working fire alarm system or sufficient and effective emergency exits. In the wake of the fire a plethora of other labour rights violations overlooked by the auditor was uncovered.

“While RINA certified the factory as safe, in reality it was a death trap that cost the life of my son and over 250 others,” said Saeeda Khatoon, Chairperson of the Ali Enterprises Factory Fire Affectees Association (AEFFAA). “We as family members and survivors are demanding justice and accountability. We are greatly disappointed by RINA’s refusal to sign the agreement.”

As an enterprise located in a member country of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) RINA must observe the organization’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. When confronted with the complaint to the Italian OECD National Contact Point (NCP) RINA rejected any liability and said it had duly audited the building according to regulations. The company said that is could not solve the issues in the auditing industry on its own and stated that the NCP process was not the right avenue to provide compensation to the affected families. The Italian OECD NCP however saw merit in the complaint and went forward to organise a mediation process.

The outcome of the lengthy mediation process was a compromise in which the NCP proposed that RINA would commit to pay 400,000 USD to those affected by the fire and that a company representative would meet with the families to express sympathy. Secondly, it suggested RINA would commit to pursuing improvement of global certification systems, such as including buyers’ purchasing practices into factory audits, as well as to improving its own due diligence practices. This would include transparency about RINA’s policies on risk management, corruption, and conflict of interest.

Believing this to be a fair compromise – even though it would not do full justice to the affected families – the complainants signed the agreement in March 2020. RINA, however, suddenly backed out of its commitment to the process and refused to sign before deadline, indicating that it saw the payments to the families as the biggest hurdle. In its final statement, the NCP recommends RINA to nevertheless make a “humanitarian gesture” towards the families in form of financial compensation and by expressing sympathy in person, as well as to proactively improve the company’s due diligence and certification practices.

“RINA’s behaviour clearly shows that we need mandatory rules on companies’ human rights due diligence that can be enforced through courts” said Miriam Saage-Maaß, head of the Business and Human Rights Programme at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR).

While the Ali Enterprises fire constitutes an especially egregious example of the failure of social auditing companies to conduct their work in the interest of workers, this case highlights many of the problems that are structural and endemic in the social auditing industry. An investigative article on RINA’s business tactics published earlier this year showed how the company consistently and structurally put profit over people, despite its professed goal of improving working conditions in the garment industry. A thorough re-haul of the full social auditing system would be needed to create meaningful improvement, including radically improved transparency and legal liability of auditing companies for their factory audits.

“Perverse incentives, lack of time, and denial of genuine participation of and information to workers create a system that serves as a buffer to protect companies’ images rather than workers,” said Deborah Lucchetti from the Italian Clean Clothes Campaign member Abiti Puliti.