Can the garment industry’s most important safety programme stay on course?

In a public brief published this week, witness signatories to the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh express their concern about the ability of this vital programme to monitor and improve the safety of Bangladeshi garment factories. 150 days since the Bangladesh-based operations of the programme were taken over by the Ready-Made-Garment Sustainability Council (RSC), this new body has not yet been able to prove that it can credibly ensure that signatories meet the obligations of the binding Accord agreement.

In 2013, just weeks after the deadly Rana Plaza collapse, brands, retailers, and global and local unions entered into a binding agreement to make Bangladesh’s notoriously unsafe garment factories safer. The five year agreement was followed in 2018 by a new binding agreement, whose Bangladesh-based operations were quickly debilitated by court proceedings started by a disgruntled factory owner, and supported by the government and garment employers’ association of Bangladesh. In May 2019, this crisis was resolved through the decision that the Accord would transition its Bangladesh-based functions to a new local organization, the RSC. While the RSC was set up to be, going forward, the implementing agent tasked with assisting the brands in meeting their obligations under the Accord agreement, it was never intended to replace the agreement itself. The Accord agreement remains in effect and unchanged until at least 2021.

Preparations for the transition of operations from the local Accord office to the RSC were hampered when the apparel industry was thrown into chaos by the Covid-19 pandemic. Calls from worker rights and safety advocates to postpone the process were ignored leading to a hasty and ill-advised transition to a body that was unprepared to fulfil its immediate responsibilities to safeguard garment workers’ safety. The RSC nonetheless began operation on 1 June with none of its senior leadership positions filled.

The four witness signatories to the Accord agreement -- Clean Clothes Campaign, International Labor Rights Forum/Global Labor Justice, Maquila Solidarity Network, and Worker Rights Consortium -- are concerned that this rushed transition and the employer influence over the RSC’s programme will threaten progress toward factory safety in Bangladesh.

These fears were exacerbated by the delay in reaching and employer attempts to weaken a cooperation agreement between the Netherlands-based secretariat of the still current Accord agreement and the RSC, needed to be able to assess whether Accord signatories are meeting their contractual obligations. The concerns especially centre around vital safeguards for the credibility and effectiveness of the Accord agreement, such as the successful continuation of the safety complaint mechanism, the Accord’s commitment to transparency and strong enforcement mechanisms, swift safety hazard remediation, and the start of a boiler safety programme.

The witness signatories, who hope that the RSC will be successful in meeting the obligations as outlined in the Accord agreement, will continue to monitor and publish a progress update on the work of the RSC. If by end of November 2020, which will mark six months since the RSC assumed its responsibilities, the RSC has not resolved the concerns outlined in this brief, the witness signatories will recommend that the Accord signatories look for another body to ensure that they can meet their contractual obligations to make Bangladeshi factories safe.

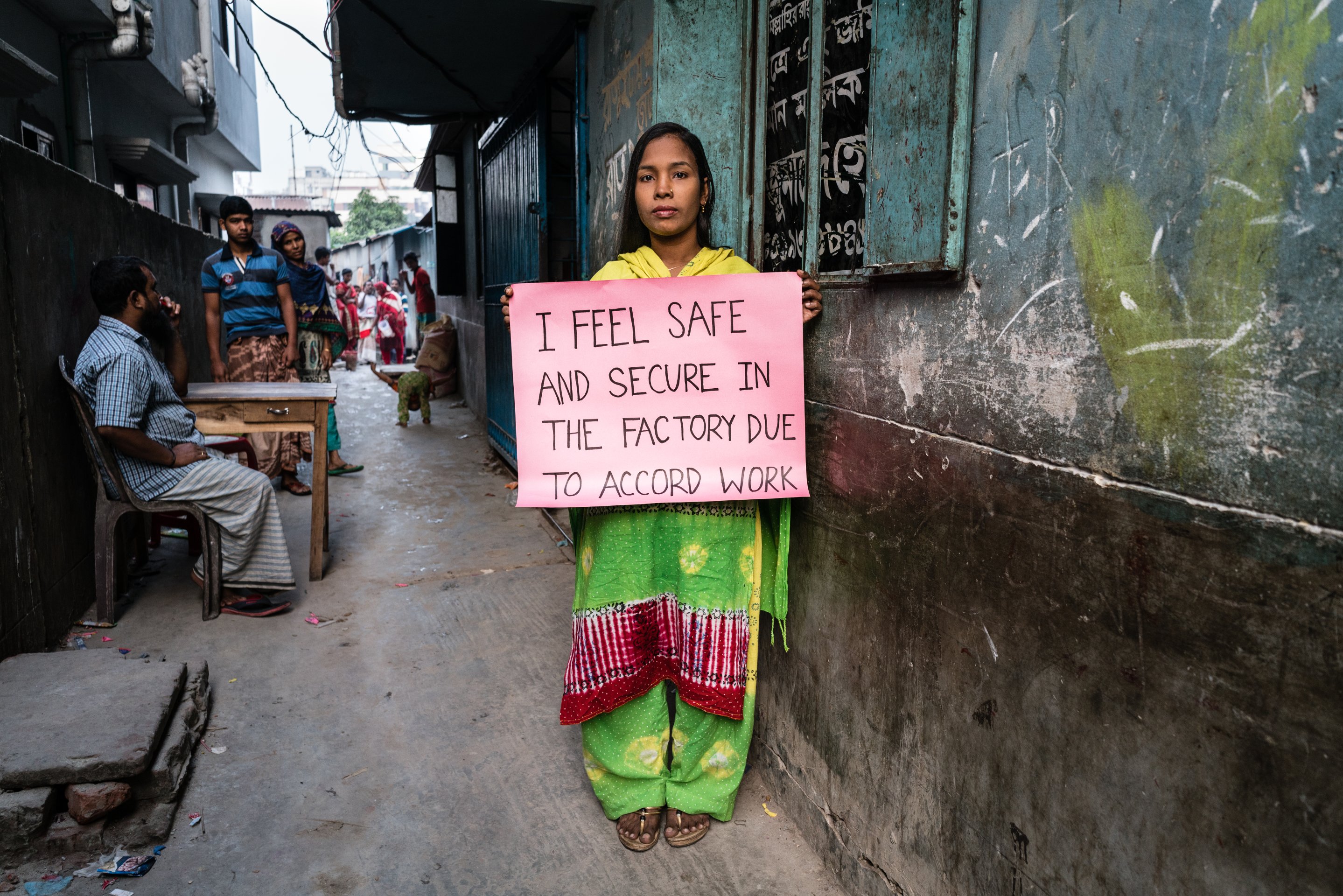

The Accord is the best example in the global garment industry of how industry, labour, and civil society stakeholders can come together and bring meaningful change to workers’ lives through a binding, credible, and transparent commitment to action. The elements of the Accord’s historic success must be preserved going forward to prevent workers from being once more exposed to deadly risk.