Seven years after deadly fire, garment workers in Pakistan still need a worker-led factory safety programme

Seven years since the Ali Enterprises factory fire of 2012, in which over 250 workers were killed, textile and garment factories in Pakistan remain as unsafe as they were then, warns a report launched today.

Initiatives established in the past years have failed to put workers and the unions that represent them in the centre of their programmes and therefore will fail to meaningfully address the industry’s safety issues. Unions and labour education organizations in Pakistan are calling for a mechanism modelled on the safety programme put into place in 2013 after Bangladesh’s deadly Rana Plaza building collapse.

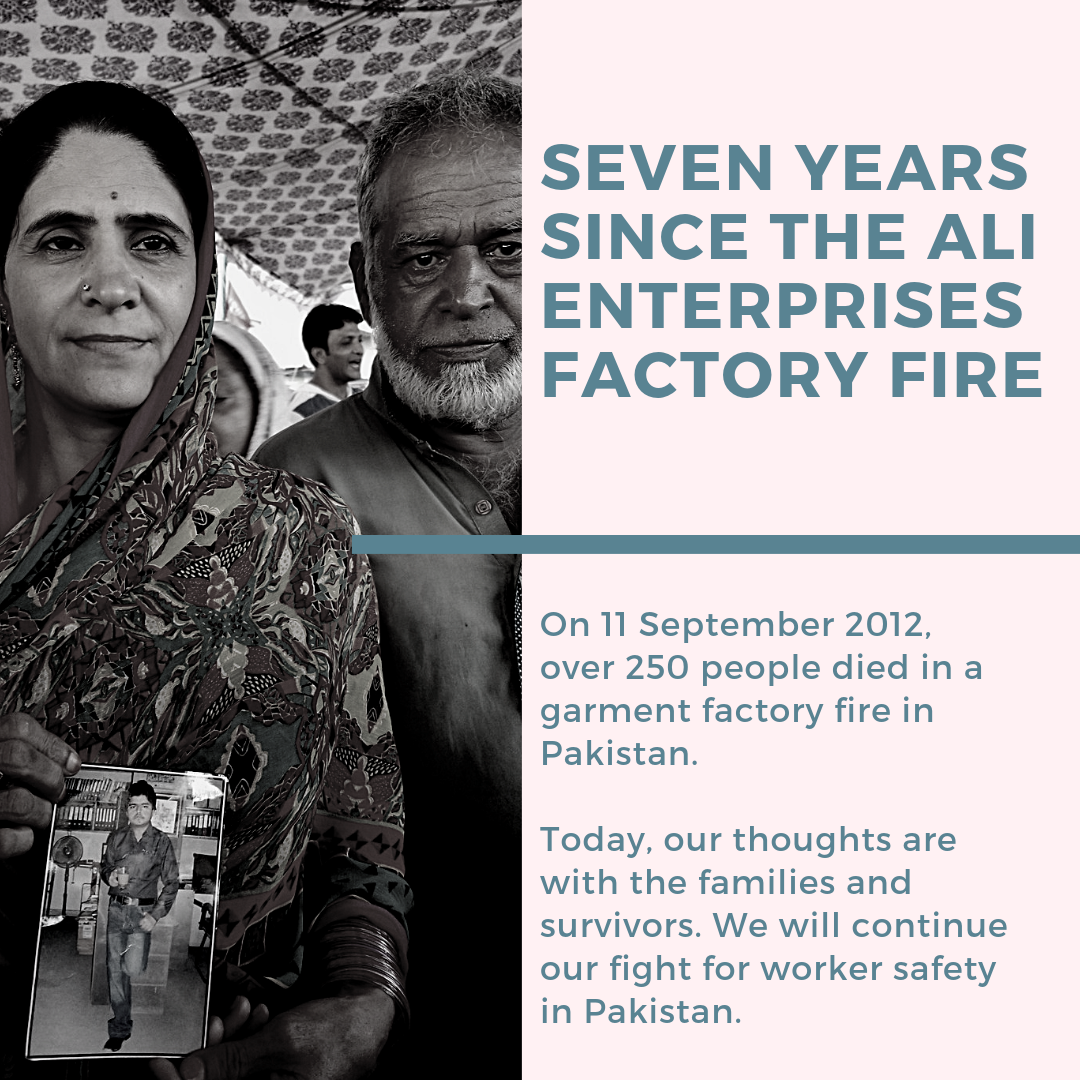

On this day our thoughts go out to all workers who lived through this traumatizing tragedy seven years ago and to the families who lost loved ones on that day. Our thoughts are also with all the workers who died or were injured in preventable factory fires and other incidents in the years after.

“The total lack of adequate safety monitoring in the Pakistan garment industry has cost hundreds of lives over recent years. Even measures that could be put into place immediately, such as ensuring workers are never locked inside factories and removing stored product away from emergency exits, could have made a difference, saving hundreds of lives in the Ali Enterprises fire and the many fires since,” says Zulfiqar Shah, Joint Director of the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research.

The report highlights that although multiple initiatives aimed at addressing workplace safety have been initiated in Pakistan since 2012, all of them have limited transparency and none are enforceable. Most importantly, none of them have been developed with the participation of unions or other labour rights groups in Pakistan. Worker representation is missing not only in their design, but also in their implementation and governance.

Brands and retailers continue to channel their energies through the very same corporate auditing schemes that have failed to meaningfully improve the industry or prevent mass casualties in the past. Pakistan’s government inspectorates remain understaffed, underfunded, and unable to meaningfully cover a growing industry. In the meantime, workers continue to risk their lives in unsafe factories and mills every day.

“Pakistan’s garment factories continue to be deathtraps. Seven years after this horrible fire, it is high time for companies whose clothes and home textiles are made in Pakistan to start taking safety for workers seriously. All stakeholders in Pakistan’s textile and garment industry, locally and internationally, must take responsibility to ensure safety for these workers, putting the people who make their products at the centre of their safety efforts,” says Nasir Mansoor, President of the Pakistani National Trade Union Federation.

The report urges brands and retailers sourcing from Pakistan to heed Pakistan’s labour movement’s calls to support the formation of a legally-binding agreement between apparel brands and local and global unions and labour rights groups to make workplaces safe. Such an agreement must draw upon lessons from the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh, which amounts to putting transparency, enforcement, commercial obligations, and worker participation at the centre of the programme. It is essential for the safety of workers that local unions and other local workers’ rights organizations be involved in the conceptualization, design, governance, and implementation of any initiatives aimed at improving occupational health and safety in the country.

“We have seen in Bangladesh, where two safety initiatives emerged at the same time, that worker-involvement, transparency, and a binding nature are vital to creating a successful safety programme. While the corporate-controlled Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety never involved independent worker-representative groups in its design, development, or governance and refused to require legally-binding commitments from companies, the Accord set a ground-breaking new standard for a transformative transparent, enforceable, and effective inspection and remediation system. Any safety programme in Pakistan must learn from and build upon those lessons,” says Ineke Zeldenrust, International Coordinator at Clean Clothes Campaign.

The report also recommends that Pakistan’s national and provincial governments take a series of steps to enhance compliance in factories that would not be covered by the foreseen labour-brand accord.

“In addition to action by apparel companies sourcing from Pakistan, it is important that national and provincial governments increase capacity, coverage, and effectiveness, in order to make sure that all garment factories and textile facilities in Pakistan become safer – not only those producing for the international market,” says Khalid Mahmood, Director of the Labour Education Foundation in Pakistan. “Currently, the Punjab government moves in the opposite direction. Its decision this month to ban factory inspections is illegal, unconstitutional, and extremely dangerous for workers. The Punjab government has justified this measure saying it would be good for business and employment. Can industry in Pakistan really only develop by violating workers’ rights and increasing the risk of factory incidents? We condemn this decision and demand the Punjab government to lift the ban on factory inspections and invest in its labour department instead.”

Lastly, the report states that governments in countries that headquarter major garment brands and retailers can and must end unaccountable self-monitoring by major actors in the garment industry by putting in place mandatory human rights due diligence legislation, thus enforcing supply chain accountability. To make a real difference in the field of worker safety social auditing firms must furthermore be held liable for faulty audits that might cost lives.

Read the full report here.