Questions raised after agreement reached on Bangladesh Accord

On 19 May 2019, the Appellate Division of the Bangladesh Supreme Court accepted a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) reached earlier this month between the Bangladesh Accord Steering Committee and the Bangladesh employers’ association in the ready-made-garment sector, BGMEA.

This memorandum concludes a period of uncertainty about the Accord’s future in the country and assures its operation for one more year, however, but does not take away the feeling of uncertainty entirely, by remaining ambiguous about the immediate impact on the workings of the Accord. It also raises questions on vital elements of the follow up institution foreseen. Media and worker representatives in Bangladesh have already posed the question whether this memorandum will weaken the Accord’s independence and give more power to factory owners. “It will have bad consequences,” Bangladeshi union leader Babul Akhter predicted to AFP.

The memorandum’s immediate impact

The agreed presence of a “BGMEA unit” within the Accord office, and the exact function of this unit, are sources of concern. According to the MoU, factories’ Corrective Action Plans will be evaluated in collaboration with this unit. This raises questions about employers’ influence over the independent decision-making processes of Accord staff. Furthermore, a visible employers’ presence inside the Accord office might negatively impact the willingness of workers to rely on its complaint mechanism, one of the most important features of the Accord.

Fears exist that the BGMEA, which has frequently publicly rejected the Accord’s work as interference into its affairs, will try to use this unit to exert undue influence on the Accord’s independent functioning against the intent of the MoU. These fears were reinforced by a recent press statement from the BGMEA, suggesting that termination and escalation of factories will require BGMEA agreement, whereas the MoU merely references “collaboration” on the escalation process. The language of the MoU is giving rise to different interpretations and more clarity is urgently required.

Questions and concerns on the RMG Sustainability Council

The MoU further announced the establishment of a permanent national monitoring safety compliance system called RMG Sustainability Council (“RSC”) which will build upon the infrastructure of the Accord, continuing its work and maintaining the same transparency levels.

The MoU does not, however, provide clarity on what will be the the new institution’s decision-making structure, finance mechanism, or enforcement mechanism - including whether this new institution will have the same legally binding nature as the Accord. This means that serious questions raised by the addition of a new stakeholder (employers) to the programme remain unaddressed; for example, whether the labour side will continue to have half of the votes in the governance structure or can soon be outvoted by brands and employers together. It is also unclear what the apparent exclusion of NGO watchdogs from this new body will mean for the future levels of transparency of this institution and how this should be interpreted in a country where trade unions' fundamental freedom to organize and speak out remain under extreme pressure. The insistence on a time-bound transition process raises the question as to what has happened to the agreement reached with the BGMEA and government of Bangladesh in 2017, which stated that the Accord would only transition its tasks to a Bangladeshi safety body if that organization could first be shown to meet strict, jointly agreed-upon readiness criteria.

For the sake of garment workers in Bangladesh, it is of utmost importance to get assurance that the new institution will operate on the same principles and criteria that make the Accord so credible and successful in keeping workers safe. This includes:

- a meticulous and transparent inspection system operating independently from any company influence;

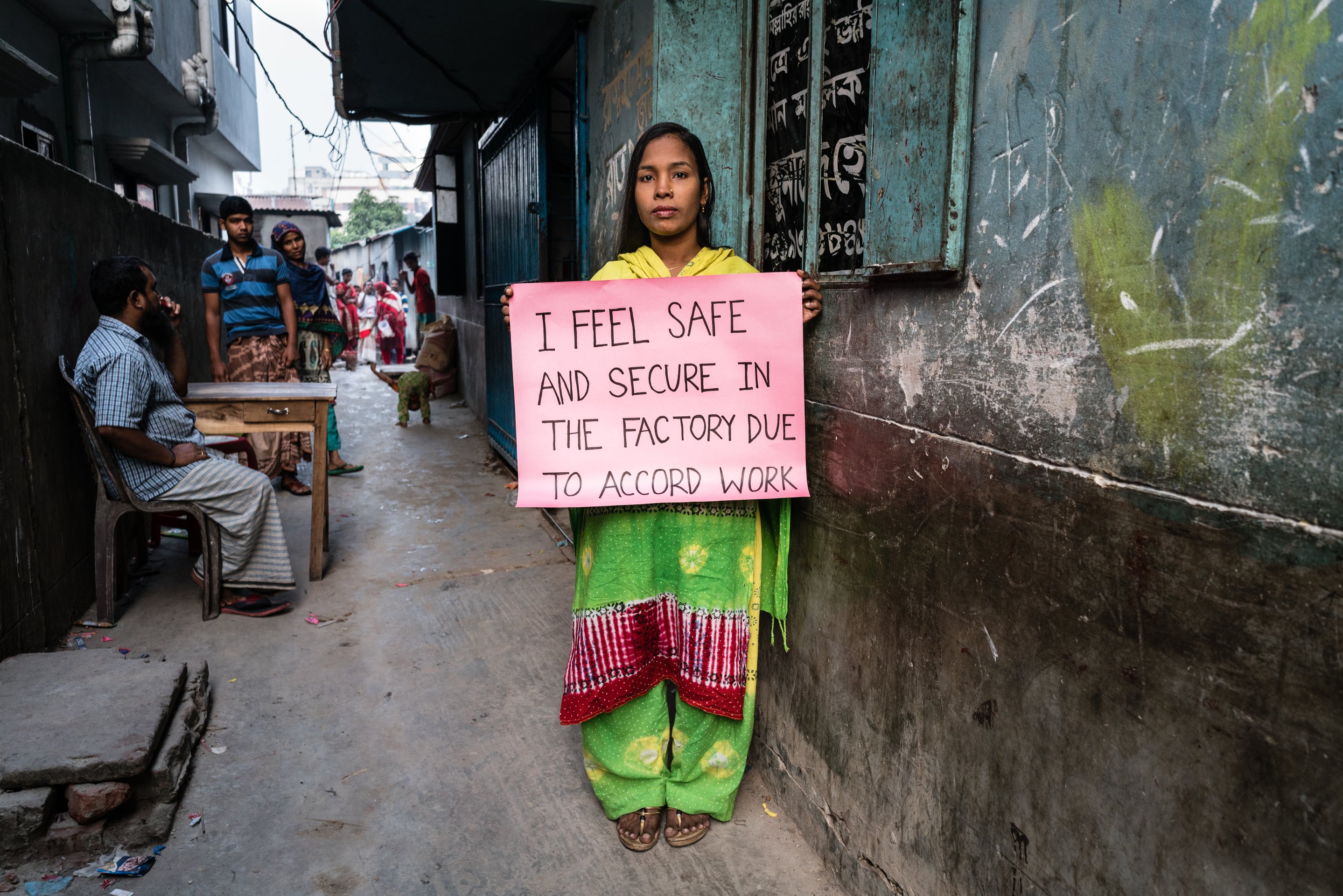

- worker trainings and a complaint mechanism that allow workers to stand up for their own safety and defend their interests against the interests of the management without having to fear retaliation;

- robust and reliable enforcement mechanisms where unions have the ability to enforce the agreement through binding arbitration; and

- a strong and independent Accord leadership in which the Chief Safety Inspector maintains full and independent discretion to make decisions on corrective actions, and scheduling (follow-up) inspections where needed.