Indonesian garment workers appeal to Uniqlo CEO in letters to take action on severance debt

Seventy ex-workers of an Indonesian garment factory, which until its illegal closure three years ago was supplying Japanese fashion giant Uniqlo, have made a personal plea to Tadashi Yanai - Uniqlo’s billionaire owner - calling on him to intervene directly to ensure they finally receive their unpaid wages and severance.

On April 22, 2015 the Jaba Garmindo factory was shuttered overnight, the owners vanished owing the 2000 garment workers – many of whom had worked there for over a decade - millions of dollars in unpaid wages and severance. As a result of tireless campaigning by these workers and their union, they were able to get partial payment from the liquidation of the company, but are still collectively owed $5.5 million. The workers have decided to write to Mr Yanai in the hope that appealing directly to one of Japan’s richest men will persuade the company to intervene and ensure they finally receive their money.

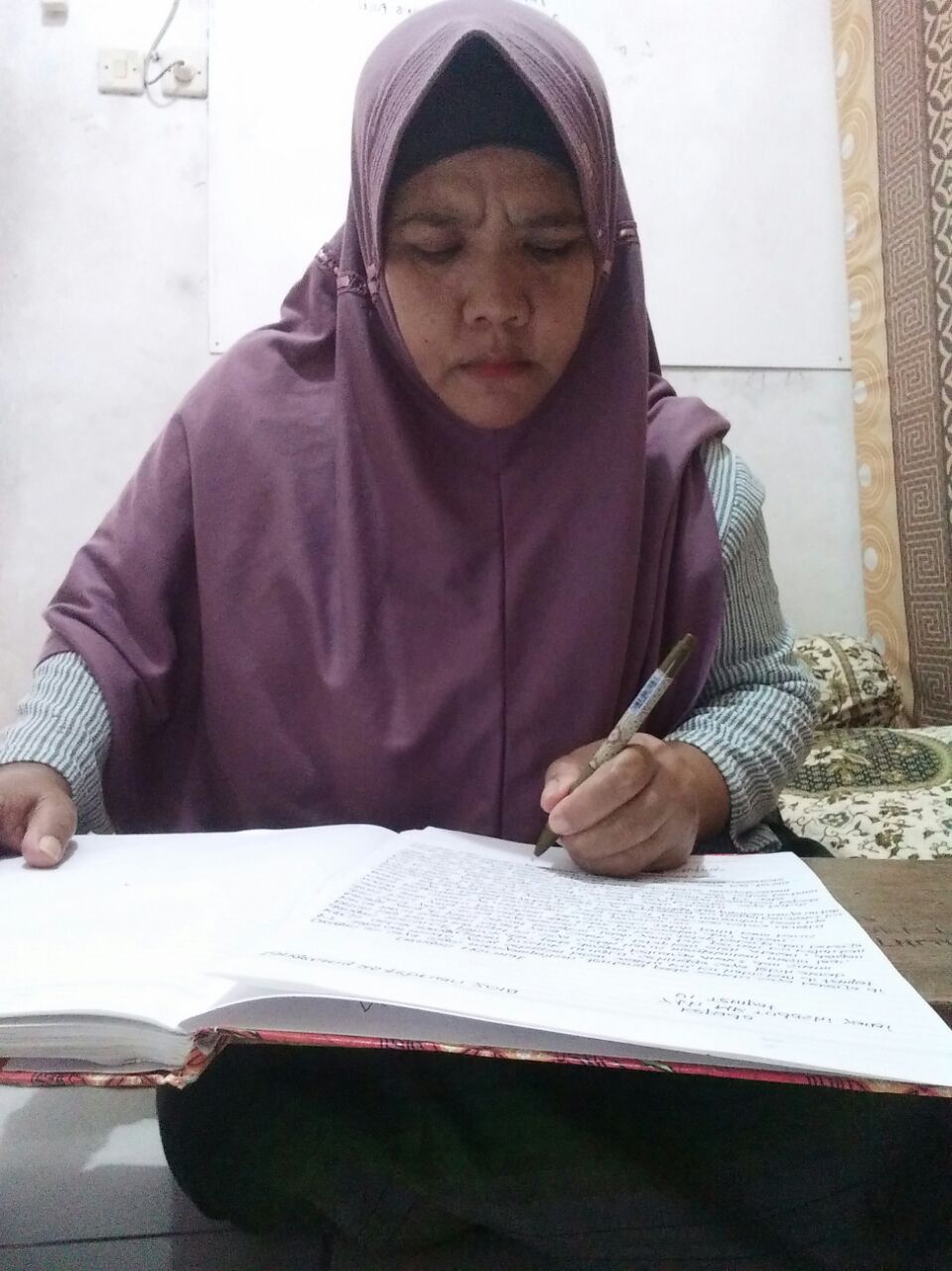

In their letters, the workers describe how hard they were forced to work to meet Uniqlo’s targets and quality standards, and how devastated they were when the factory closed.

In her letter Anik tells Mr Yanani: “When I was employed at Jaba Garmindo, I spent most of my time there creating Uniqlo products. Even on my days off I came in to operate machines because we had to meet the target as set by you, by Uniqlo. I ignored my pain as much as I could to reach these results so we would not get scolded by our boss.”

The letters also recount the story of what happened to their factory, the impact the closure has had on their families and the efforts they have made to recover the money they are owed. They are hoping that their personal appeals will persuade the Japanese billionaire to finally take action on their case.

Jarsidiq says in his letter: “You have to know what impact Jaba Garmindo’s bankruptcy has had on us. You did not try to prevent this closure. You pulled out orders from Jaba Garmindo and just left this factory without care for workers. Now we have lost our jobs, our livelihood and it is impacting our children because they can’t continue their study. We are struggling now for over 3 years. You don’t know how hard our struggle has been to end this.”

Hariyadi’s letter says: “When Jaba Garmindo went bankrupt, I became extremely depressed. I am too old to find another job and I am struggling to meet my daily needs. I worked for twenty years at Jaba Garmindo and I am now 55. I have no job and I want my wages to be able to start a business, meet my daily costs and support my children to continue studying.”

Fast Retailing, the parent company of UNIQLO, is now the third largest clothing retailer in the world, having posted a profit forecast of $2.11 billon this year. Tadashi Yanai has stated his ambition to become the biggest brand in the world, which would mean overtaking Spanish giant Inditex (owners of Zara) and Swedish brand H&M. He has promoted an aggressive growth plan, which includes significant expansion in Europe. Earlier this year UNIQLO launched a huge flagship store in Barcelona; a similar store is due to open in Stockholm’s main shopping street later this year. This expansion is combined with lowering both price and production times; UNIQLO now demands “design to delivery” times of just thirteen days.

International labour activists from the Clean Clothes Campaign in Europe and Asia are supporting the Jaba Garmindo workers in their demands for payments and are urging Mr Yanai to listen to their workers and take immediate action to rectify the injustice they have suffered.

Many of UNIQLO’s closest competitors have taken such action in similar cases. Nike, adidas, Disney, Fruit of the Loom, Hanesbrands, H&M, and Walmart have all taken active steps to ensure that workers received wages and severance payments owed when supplier factories went bankrupt, by either directly provided the funds owed to workers themselves, or pressing their supply chain partners (factory owners, buying agents, etc.) to do so, so that the workers received the sums that they were due under law.