New report: false promises and restriction of movement in production for Western garment brands

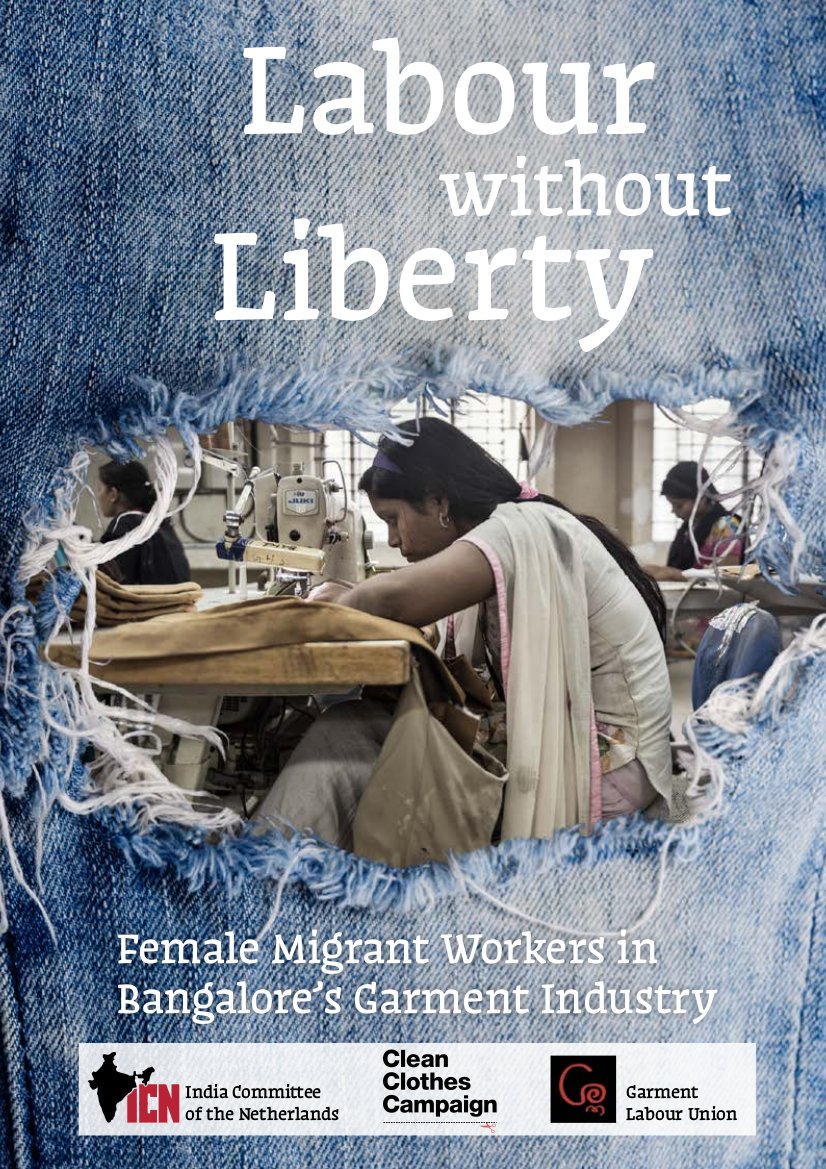

Female migrants employed in India’s garment factories supplying to big international brands like Benetton, C&A, GAP, H&M, Levi’s, M&S and PVH, are subject to conditions of modern slavery. In Bangalore, India’s biggest garment producing hub, young women are recruited with false promises about wages and benefits, they work in garment factories under high-pressure for low wages. Their living conditions in hostels are poor and their freedom of movement is severely restricted. Claiming to be eighteen at least, many workers look much younger.

These are some conclusions from the report ‘Labour Without Liberty – Female Migrant Workers in Bangalore's Garment Industry’. The study found that five out of the eleven ILO indicators for forced labour exist in the Bangalore garment industry: abuse of vulnerability, deception as a result of false promises (wages etc.), restriction of movement in the hostel, intimidation and threats, and abusive working and living conditions. Some of these aspects are also felt to a certain extent by the local workforce, but are more strongly experienced by migrant workers.

The researched factories and their buyers

The three factories in the research belong to the largest garment manufacturing companies in Bangalore. Together they employ more than 4000 workers in various units in the country. According to export data these are their buyers: Abercrombie & Fitch, Benetton, C&A, Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger (both PVH), Columbia Sportswear, Decathlon, Gap, H&M, Levi Strauss, Marks & Spencer. Most of these brands have code of conducts that prohibit forced labour, child labour and other labour rights violations.

In responding to an ICN report ‘Unfree and Unfair’ from January 2016 on the living and working conditions of migrants in Bangalore, C&A, GAP, H&M and PVH responded with some concrete commitments. Though there has been research by them affirming the findings of ‘Unfree and Unfair’ and a meeting with suppliers, after almost two years most of their commitments still have to be put in practice.

Review reactions to the present report vary greatly. Abercrombie & Fitch did not respond at all. Other brands like Benetton, Columbia, H&M and M&S gave very brief responses while Decathlon, Gap, Levi and PVH responded in more detail. Unlike C&A, H&M, PVH and Inditex, brands like Benneton and Levi’s do not acknowledge the issue.

Uma comes from a small village in northern states of India like many of her young colleagues. She was recruited and trained to go work into one of the 1200 factories in Bangalore, the ‘textile capital’ of India. Uma used to go to school and help her mother, now she stitches dresses and sportswear for H&M, Benetton, C&A, Calvin Klein and many other big international brands. Six full days a week. The target is hundred pieces per hour. For a minor like she is - her mates reminded her she was 18, but she turned out to be only fifteen - work at the factory in a faraway city is difficult. She misses her family and friends, who are thousands of kilometres away.

Migrant workers in Bangalore: vulnerability and abuse

Uma, her name has been changed for safety reasons, was among the workers interviewed for a new investigation into the working and living conditions of migrant workers in three garment factories in Bangalore.

Official statistics on migrants do not exist, but trade unions estimate that there are between 15,000 and 70,000 migrant women from northern states working in the Bangalore garment industry. Before travelling to the factories, they are trained in skill development centres in Jharkhand or Odisha. These centres are often part of government sponsored schemes which fall under Skill India. Skill enhancement is one of the pillars of ‘Make in India’, prime Minister Modi’s major initiative to create employment opportunities and stimulate economic growth.

Recruitment agents are known for not informing recruits about their legal entitlements. They promise salaries ranging from about € 65 to € 105 and other benefits like free accommodation and food. But upon arrival in the factories, these promises often appear to be false. Migrants find themselves earning less than they were told, having to pay for accommodation and food. Migrant workers live in hostels with cramped rooms. They are not allowed to leave on weekday evenings. Only at Sundays they are allowed two to three hours away from the hostel grounds.

Many workers, although claiming to be eighteen or older look young enough to be fifteen or sixteen.

Many migrant workers reported being shouted at by supervisors in the local language of Bangalore, which they do not speak and they are repeatedly pushed to work faster. This was confirmed by all seven local workers, who observed that supervisors treat migrants badly and insult them using vulgar words. According to them, migrant girls often cry when this happens.

Read the full version and the abstract of the report.