Nike, adidas and Puma's workers earn poverty wages to pay for European championship endorsements

The three main sportswear sponsors of the UEFA European championship 2016, Nike, adidas and Puma, pay poverty wages to the workers that stitch their shirts, shows a report by Collectif Ethique sur l’étiquette (Clean Clothes Campaign in France), presented in English today. The report ‘Foul Play’ exposes the adverse impact on workers of a business model based on low labour costs and relocation to countries with the lowest wages and weak labour regulation. At the same time these brands invest massively in endorsement deals with players, national teams and clubs. Nike, adidas and Puma's prime concern is economic performance and profit, which will be considerable during the European championship, while the workers come off worst.

Dominated by the Big Three—Nike, adidas and Puma—European football endorsements have reached astronomical levels: deals made with the 10 biggest teams have risen from €262 to more than €405 million since 2013. Nike became the industry leader, doubling its dividends since 2010. In an attempt to catch up, adidas and Puma have reacted by entering a race for profitability. To increase profit margins, these brands have to sell more products to more consumers than ever before – Nike, the industry leader, has doubled its sales in less than 10 years. This constant growth requires large investments in innovation and an ever-increasing media presence, notably through endorsements.

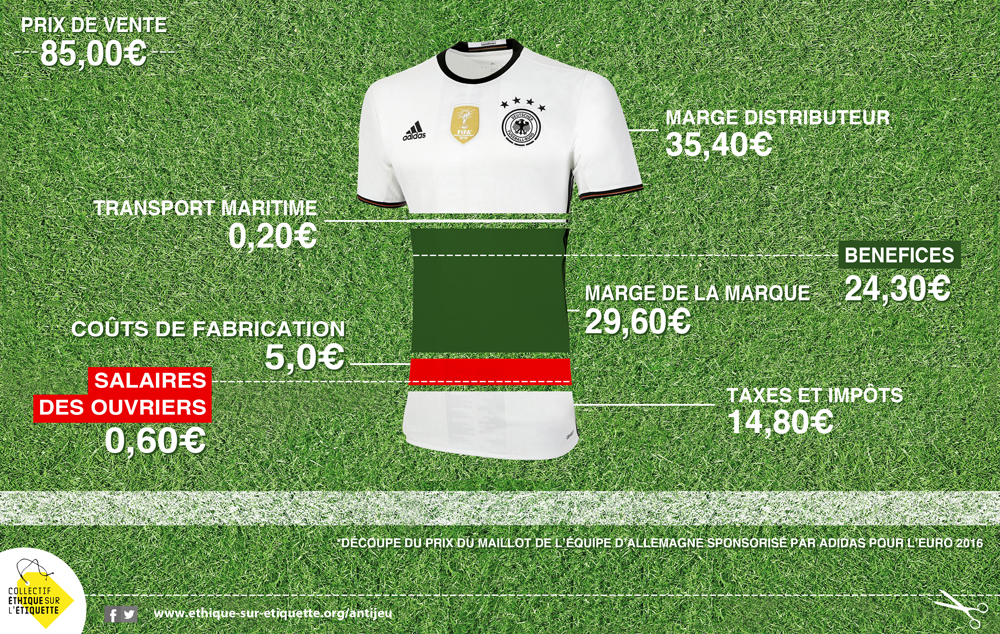

Starting in the 2000s, the big sportswear brands implemented a new system of supply chain management, allowing them to diversify their product line while integrating technological innovations. These systems allow for optimized cost control: for each shoe model the sportswear brands set their desired retail price and profit margin, and from there calculate the maximum production cost for the item. They then sit down with their suppliers to determine which raw materials to use, their origin and price, as well as the exact number of minutes allotted to manufacturing and how much workers are to be paid. This leads to situations as the production of the German football team shirts, which is sold for 85 euro: 60 cents goes to the garment worker, while a profit of 24.3 euro goes to adidas.

A bad business model for workers

Within this tight system of cost control the workers come off worst, earning wages too low to meet their basic needs. This contradicts the public declarations of these sponsors that position themselves as more responsible brands than others in the sector. The report however shows these sportswear brands are massively shifting their sourcing from China, where wages have seen significant increases, to Vietnam, Indonesia, and soon also to Myanmar, India and Pakistan, where lower wages allow for significant labour cost savings.

In this way, they expose themselves to significant breaches in labour standards (unpaid overtime, no paid vacation, discrimination and impediments to organized labour). They try to curb these issues through an increasingly sophisticated and costly system of labour audits which however does little to address the main problems.

Paying a living wage would represent only a few dozen cents more in the final price tag of a pair of sneakers or a sports jersey. But it is the system of infinitesimal savings on millions of items that allows the Big Three to invest lavishly in their constantly ballooning marketing budgets, and their “sneaker wars” on the sports field. The endorsement costs of the ten largest European football clubs since 2013 would have been sufficient to pay living wages to 165,000 workers in Vietnam and 110,000 workers in Indonesia.

Transnational companies should be responsible for their full supply chain

During the European championship Collectif Ethique sur l’étiquette, supported by Clean Clothes Campaigns in several other European countries, takes action to remind transnational brands of their responsibility to respect fundamental labour rights and demand the big sportswear brands to adopt purchasing practices that allow a living wage for workers, who contribute so much to their profits. It stresses the importance of legally binding regulation, such as the bill on due diligence due to pass in France, to hold transnational companies responsible for their full supply chains.

Read the report here.