Q&A on the International Accord

This Q&A explains what sets the International Accord apart, what the work in Bangladesh looks like, how the Accord is expanding, where the Accord came from and why we need to campaign.

1. The International Accord

What is the International Accord?

The first International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry took effect on 1 September 2021 (download the text here). It is a legally binding programme, which garment brands can sign on to ensure that garment factories in their supply chain are made safe. The second international agreement was reached in November 2023. Currently the Accord only has a programme in Bangladesh, but it has the ambition to expand to other countries. The International Accord is governed by a Steering Committee which consists of 50% brand representatives and 50% union representatives. Labour rights NGOs (including Clean Clothes Campaign) have signed on as witnesses and participate in the Steering Committee as observer.

How does the International Accord differ from its predecessor the Bangladesh Accord?

The International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry’s most important differences are laid down in the name: i) the programme will no longer be limited to one country, but will expand to at least one other country beyond Bangladesh, ii) the programme no longer only focuses on building safety, but has a broader mandate, addressing health and safety of workers in general. The text of the International Accord can be found here.

How many signatories does the International Accord have?

Find the latest on https://internationalaccord.org/signatories.

Which major brands did and which did not sign the International Accord?

Find out more on cleanclothes.org/accord-tracker.

Is the Accord only about inspecting and fixing factories?

No, beyond making factories safer by inspecting and remediating, the Accord signatories also seek to use the programme to empower workers and local trade unions by informing them about their rights to a safe and healthy workplace. The Accord prescribes a Safety Training programme for workers and joint worker-management Safety Committees at covered factories; and provides workers and their trade unions with an independent Occupational Health and Safety complaints mechanism, which allows them to raise workplace safety issues that the factory management are then required to remediate.

How does the Accord ensure that brands and factories do what is promised in the agreement?

The Accord’s legally binding nature is key to its effectiveness. The Accord model prescribes two levels of enforcement: i) at the factory level, through an escalation process, where a factory that does not remediate safety issues can face termination of business with all Accord company signatories; and ii) at the brand level, through a dispute resolution clause, allowing the union signatories to file arbitration charges against the signatory brands which do not meet their obligations under the Accord agreement.

All Accord signatory companies are required to comply with the Accord’s provisions, including requiring their suppliers to participate in the inspection and remediation programme as well as in the worker empowerment programme, and ensuring that remediation at their suppliers is financially feasible. The shared commitment means that brands can effectively use their collective leverage to advance workplace safety.

In 2016, IndustriALL and UNI Global Unions brought arbitration cases against two Accord signatory companies for failure to ensure that remediation at their suppliers is financially feasible. These resulted in settlements of over US$2 million paid towards safety remediation.

2. The work in Bangladesh

How is the International Accord’s work in Bangladesh organised?

The activities in Bangladesh on the ground, including factory inspections, monitoring the safety remediation, conducting safety training at the covered factories, and providing workers with an independent complaints mechanism, are carried out by the RMG Sustainability Council (RSC). The RSC is governed by a tripartite board of brands, trade unions, and manufacturers, but does not have any means to hold brands accountable.

The International Accord provides that additional feature. It is a binding contract between brands and unions, which means that unions can, on the basis of the information from the RSC’s inspections, remediation checks and the complaint mechanism, start an enforcement procedure against brands. This can end up in court, as the final step. In the past this has led to two settlements.

Why is there an International Accord and a RMG Sustainability Council (RSC)?

After its founding in 2013, the Accord was established as a foundation in The Netherlands and as an office in Bangladesh, employing about 200 staff. In 2018 and 2019, a protracted court proceeding against the in-country office by a disgruntled factory owner led to the creation of a new national implementation organisation, the RSC, which took over operations on the ground on 1 June 2020. It was agreed that the RSC would implement all Accord standards, policies and procedures.

The RSC, which is a non-profit company with a board of directors made up of brands, unions, and employers, however does not have the power to hold brands legally accountable to ensure remediation in the factories they source from is fulfilled per the agreed standards, policies and procedures. This includes that remediation needs to be financially feasible – which is an obligation laid down in and enforceable through the International Accord. The International Accord is therefore direly needed so that brands do not only commit to factory safety to look good, but can be held accountable if they are not meaningfully contributing to safer factories.

The unions, which make up 50% of the governance in the Accord, but only one third of the RSC governance, have indicated they think this ability to hold brands accountable is crucial to the success of the inspection, remediation and complaint-handling work by the RSC.

As the RSC does not have any means to hold brands accountable to ensure remediation in the factories they source from is financially feasible, this obligation is laid down in and enforceable through the International Accord.

If a factory refuses to cooperate in the inspections or carry out remediation, the RSC can take measures against those factories (but not against brands), including withdrawing their export licenses. The International Accord can additionally as a final measure also require factories to be terminated, meaning that no Accord member brand is allowed to source from that factory.

The International Accord can thus hold brands to account. The International Accord Secretariat’s mandate is to monitor the implementation of the signatories’ obligations in Bangladesh as reported by the RSC.

The Centre on Policy Dialogue in Bangladesh in April 2023 released a report about the work of the RSC, including concerns about its transparency.

How many factories are covered by the International Accord in Bangladesh?

ca. 1500.

3. International expansion

What does the “International” in International Accord mean?

The International Accord allows for the development and implementation of country-specific fire and building safety programmes in other countries in addition to the existing Bangladesh programme. In December 2022 the Pakistan Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry was announced.

Prior to that the Accord Steering Committee conducted a feasibility study to assess safety risks, signatory presence, regulatory and implementation gaps and interest in a range of countries and carried out country visits. The exact form and implementation of the programme in each country will be assessed per country, and therefore it will look differently from how implementation is organised in Bangladesh.

Expansion to other countries beyond Bangladesh and Pakistan is needed, as workers in many other countries such as Morocco and India still face very unsafe working conditions.

Why is expansion needed?

The garment industry is notoriously unsafe. It is high time that brands take responsibility for the working conditions in their garment supply chains beyond Bangladesh. A few examples of major workplace incidents in 2021 include 28 workers being killed by electrocution in an illegal garment factory in Morocco in February 2021, 20 workers killed in a fire at a garment factory in Egypt in March 2021, 8 people killed in a collapse later that month in the same country, and 16 people killed in Pakistan in August 2021.

Clean Clothes Campaign published a timeline highlighting just the tip of the iceberg of fatal and near fatal incidents in garment and textile factories around the world since the start of 2021: cleanclothes.org/incidents-timeline.

4. Alternatives

What distinguishes the International Accord from other programmes?

Contrary to commercial social auditing, brand-led programmes, and unenforceable multi-stakeholder initiatives, the Accord is legally binding. This means that all Accord signatory companies must comply with the Accord’s provisions and that the Accord trade union signatories can start a procedure against non-compliant companies.

The Accord has been successful preventing mass casualties in the garment industry where other programmes have failed because of a unique combination of elements: its legally-binding nature, bi-partite governance (brands & unions on the Steering Committee), the brands’ collective leverage, high levels of transparency and disclosure, brands’ obligations to financially support the remediation, and an independent complaints mechanism. The Accord is the only initiative in the global garment industry through which brands and worker representatives can work together at a large scale and on an equal footing to make tangible progress towards a safer industry.

Under the Accord, signatory brands have an obligation to ensure that factories are financially able to address the safety issues identified at their factories. This is a groundbreaking aspect of the Accord model, as it contributes to achieving more sustainable sourcing practices, where the costs of maintaining a safe workplace is made part of the business relation between brands and factories.

Furthermore, the Accord’s complaints mechanism, in contrast with many voluntary MSI’s complaints mechanisms, is widely trusted by workers and has demonstrably prevented accidents and ensured the reinstatement of workers who were dismissed for raising the lack of safety in their workplace.

What is the problem with brand-owned initiatives (for example IKEA’s IWAY) and commercial social auditing?

In contrast, voluntary initiatives have in the past been unable to prevent mass casualties, and it is therefore completely irresponsible to fall back on trusting a non-enforceable initiative to prevent a new Tazreen fire (2012) or Rana Plaza collapse. The problem with brand-owned and commercial social auditing systems is that there is no independent oversight, nor any incentive to be transparent or work towards real change. Basically the company is checking its own behaviour, or paying someone who is geared towards pleasing its customer to check its behaviour. As there is no transparency companies can easily ignore any unfavourable outcomes or decide to leave a factory that is unsafe without fixing it. Workers won’t be informed that their factory is unsafe, nor will any other or new brands sourcing from this factory. These are only some of the major issues that haunt the commercial social auditing system.

What is Nirapon and why is it not good enough?

In 2013, after the Rana Plaza collapse, it was clear to all garment companies sourcing in Bangladesh that something needed to be done to address factory safety in the country. Not all companies were ready to commit to the legally binding Accord, with its union participation and high level of transparency. A group of primarily US based companies established their own alternative without these same features, which was called the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. Lacking the Accord’s crucial elements of accountability and transparency, research showed that remediation progress of factories under the Alliance could not match that of the Accord.

Contrary to the Accord, which after the first five years recognised that the work was not done, the Alliance wrapped up its work in 2018 and instead put in place a stripped down programme, called Nirapon. Nirapon claims it conducts monitoring, a helpline (amader kotha), and trainings in 600+ factories.

Both the Alliance and Nirapon were run by a well known commercial auditing firm called Elevate. Contrary to the Accord, in Nirapon, the brands don’t play a role in ensuring safety hazards can be (financially) addressed by factory owners. The Elevate website says: “The ownership of risk rests with the employer, and only the owner of risk can effectively control that risk – not the customer. That means that if a factory is not safe, we can only provide the owner and managers with the education and direction to achieve a safe workplace, we cannot control the risk for them.”

Furthermore, Nirapon provides no transparency about its operation. A recent research from a Bangladesh research institution shows that virtually no information is available on what Nirapon has achieved.

In October 2019, in the wake of the court cases that had haunted the Accord’s Bangladesh-based office, a court in Bangladesh put a six month ban on Nirapon’s operations in the country, in response to factory owners’ conviction that such safety mechanisms were no longer needed and only created additional costs for factories. On 31 May 2020, the day before the establishment of the RSC, Nirapon announced to shift operations to North America. It remains unclear whether the ban has been lifted and whether the move to the US is connected to this, as well as what this means for implementation on the ground, which might be left to employers’ discretion only.

The almost 50 brands that are members of Nirapon include Gap, VF Corporation (The North Face, Timberland), Walmart, Asda, Canadian Tire, Disney, Abercrombie & Fitch.

5. Background

How did the Accord come about?

The legally binding Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh (“Bangladesh Accord”) between apparel brands and global trade unions was established in the aftermath of the Rana Plaza collapse of 24 April 2013 and was meant to make factories safer for workers. Over 200 international brands and retailers signed the first Accord agreement, including H&M, Inditex (parent company of Zara), C&A and Primark. The Accord is a legally-binding agreement between brands and retailers and IndustriALL Global Union & UNI Global Union and eight of their Bangladeshi affiliated unions. Together, the parties have committed to the goal of a safe and sustainable Bangladeshi ready-made garment industry in which no worker needs to fear fires, building collapses, or other accidents that could be prevented with reasonable health and safety measures.

What has the Accord achieved and why is it still needed?

The Accord has brought crucial improvements to the lives of 2 million garment workers in Bangladesh, making 1,600 garment factories safer, and has created an effective and transparent complaint mechanism that is allowing workers to stand up for their own safety. Since 2013, Accord engineers have carried out over 38,000 inspections. Over 120,000 fire, building and electrical hazards have been fixed. The remediation progress rate at Accord factories is at 93 percent. More than 1.8 million workers have been trained in workplace safety. Workers or their representatives have made over 3,000 grievances through the health and safety complaints mechanism, of which over 270 are related to Covid-19.

But, the work is not yet done. Many factories still have to carry out vital safety remediations and constant inspections will remain needed to ensure factories don’t return to unsafe practices such as putting finished product in front of emergency exits. Despite all the work done, the programme remains as needed as ever.

And even if all safety violations would have been remediated, a meaningful safety monitoring and remediation system would remain vital. Safety is a continuous process, and not only does continuous monitoring reveal new safety defects to remediate, also is it an important measure against the return of dangerous practices, such as storing finished product in the way of safe egress.

6. Target Brands

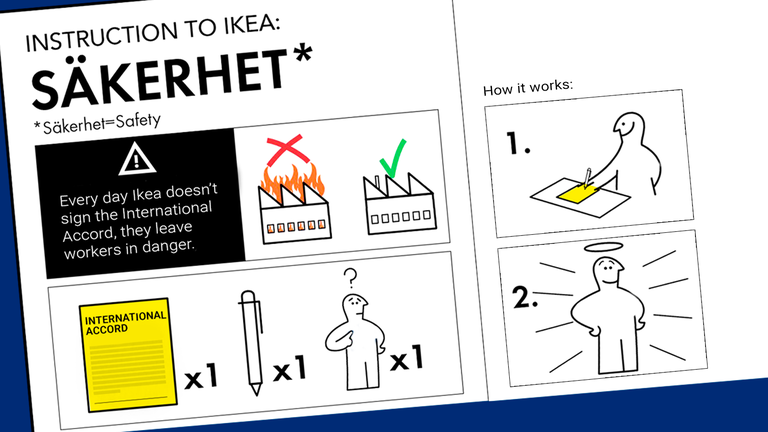

Why are we targeting IKEA?

IKEA is not transparent about its supply chain, but it sources its home textile from several factories in Bangladesh and other high-risk countries like Pakistan. IKEA has been called upon to sign the Accord since the agreement expanded to include home textile production in 2018, but has always maintained that its own code of conduct, called the IKEA Way or IWAY is equally effective or even more effective in making factories safe. IWAY has no independent oversight, no enforceability, no worker participation and no transparency. IKEA is literally doing things “its way”, is checking itself whether it lives up to its own standards, and will tell no one if it doesn’t.

Why are we targeting Levi's?

According to its latest factory list, Levi’s has 27 supplier factories in Bangladesh, and 34 in Pakistan. The company has not signed the previous Accords of 2013 and 2018. Our research shows that Levi’s is sourcing from a range of factories in Bangladesh where Accord signatories like Fast Retailing (Uniqlo), Next, Varner, G-Star and Sainsbury’s ensure that safety renovations are financially possible and Levi’s is free-riding on their efforts.

In response to an earlier call to sign the Accord, Levi’s spokespeople in November 2021 stated that “in 2009, we forbade working with suppliers operating in multi-level, multi-owner buildings, where safety standards are difficult to enforce.” While this statement could create the impression that Levi’s does not source from the typical multi-storey building that most garment factories are housed in in Bangladesh, this is not the case. The statement only indicates that Levi’s does not source from buildings where there are several differently owned factories in the building. While this takes away one risk-factor, it does not say anything about the structural integrity of the factory they source from, nor about any other safety risks.

Why are we targeting Auchan?

Auchan has previously signed the Bangladesh Accord in 2013 and 2018 but has thus far failed to take the step to sign the International Accord. This is surprising as Auchan was one of the companies which sourced from a factory in the Rana Plaza building and it therefore knows full well what can happen without a thorough safety programme. Auchan is not transparent about its supplier list, but in a recent research paper we managed to identify at least 30 factories that produce for Auchan in Bangladesh. In the same paper, we also argue that Auchan could be held legally liable for not living up to its obligations under the French Duty of Vigilance law if Auchan does not re-sign the Accord. A recent research by Action Aid France also shows that Auchan cannot fall back on social auditing, as there are major issues with in, in general and its supply chain in particular. In 2015, Auchan was sued by Sherpa, Ethique sur l’Etiquette (CCC member in France) and Action Aid for "misleading commercial practices" in connection to its presence at Rana Plaza.

What's next?

The Clean Clothes Campaign network will continue to push sourcing from Bangladesh to sign the Accord. The campaign will continue to target both brands that did sign the Accord before, or were even producing in the Rana Plaza building, but that failed to sign the new agreement, as well as brands who have never signed a previous Accord agreement and are instead relying on their own accountability systems, corporate social auditing or unenforceable collective systems such as Nirapon.