BLOG - Nine years since deadly fire at major Walmart supplier, campaigners urge Walmart to stop hiding from real commitments to safety

Exactly nine years ago, a devastating factory fire in Bangladesh killed at least 113 workers and injured many more. Almost a decade later, major brands and retailers whose clothes were made in this factory, such as Walmart, Disney, and Dickies, continue to put their workers at risk. We spend this day commemorating the workers who died in this preventable fire. In addition, we are continuing to remind garment brands and retailers that they must finally draw lessons from this horrific catastrophe and urgently take critical steps to prevent future fires and deadly safety incidents so that no more families have to suffer such an awful loss.

When on 24 November 2012 the Tazreen Fashions garment factory in Dhaka caught fire, the manifestly unsafe factory trapped workers in smoke and flames. For many workers, there was no other escape route than to jump from upper floors. The Tazreen fire followed a decade of smaller factory tragedies in the country that cumulatively had killed at least 500 workers. Five months later, it was overshadowed by the even more deadly Rana Plaza collapse, which killed over 1,100 garment workers.

Both tragedies provided the final push for a group of garment brands and retailers to agree to sign a binding agreement with unions that established the Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh: a transparent and credible initiative that has since made factories safer for over two million workers in the last eight years.

Some brands and retailers, however, outright refused to heed the wake-up call and ignored unions’ appeals to work together, instead creating their own corporate-controlled, non-transparent initiative in an attempt to shield themselves from criticism over their failure to address factory safety. These companies include Walmart and Disney, whose products were on several production lines at Tazreen at the time of the fire, but also other major US brands and retailers with significant production in Bangladesh, such as Gap, VF Corporation (The North Face, Timberland), and Target.

These companies’ go-it-alone program (the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety), closed business after five years, keeping in place a stripped down version of its activities, called Nirapon. There is no evidence that Nirapon is much more than a façade that its member brands can point at if anyone questions them about the safety of their factories in Bangladesh and why they have not joined the Accord. Since late 2019, Nirapon no longer has operations in Bangladesh and it now exists within the office of corporate social auditor Elevate in the United States.

The effect of this social auditing firm is to shield brands from any responsibility or accountability whatsoever by putting the responsibility for solving any identified safety risks on the factory owners alone. The Elevate website says: “The ownership of risk rests with the employer, and only the owner of risk can effectively control that risk – not the customer. That means that if a factory is not safe, we can only provide the owner and managers with the education and direction to achieve a safe workplace, we cannot control the risk for them.” This is a radically different approach than that of the Accord, which has always put the obligation on member brands to ensure that their supplier factories have the financial means to carry out the prescribed safety renovations and repairs.

Retailers like Walmart, whose reliance on non-transparent and corporate-controlled social auditing has had deadly consequences in the past – as shown in Tazreen Fashions on 24 November 2012 – should know better. Fortunately, the Accord has now, as of September, started a new mandate in the form of the International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry to continue its work for two years and expand its coverage to encompass more health and safety issues, in addition to fire and building safety, as well as start new programmes outside of Bangladesh. This is the moment for retailers like Walmart to change their minds, stop hiding behind a façade of corporate rhetoric, and start being part of the initiative that is actually making factories in garment supply chains safer, saving hundreds of lives.

Authored by Christie Miedema for Apparel Insider

25 November 2021

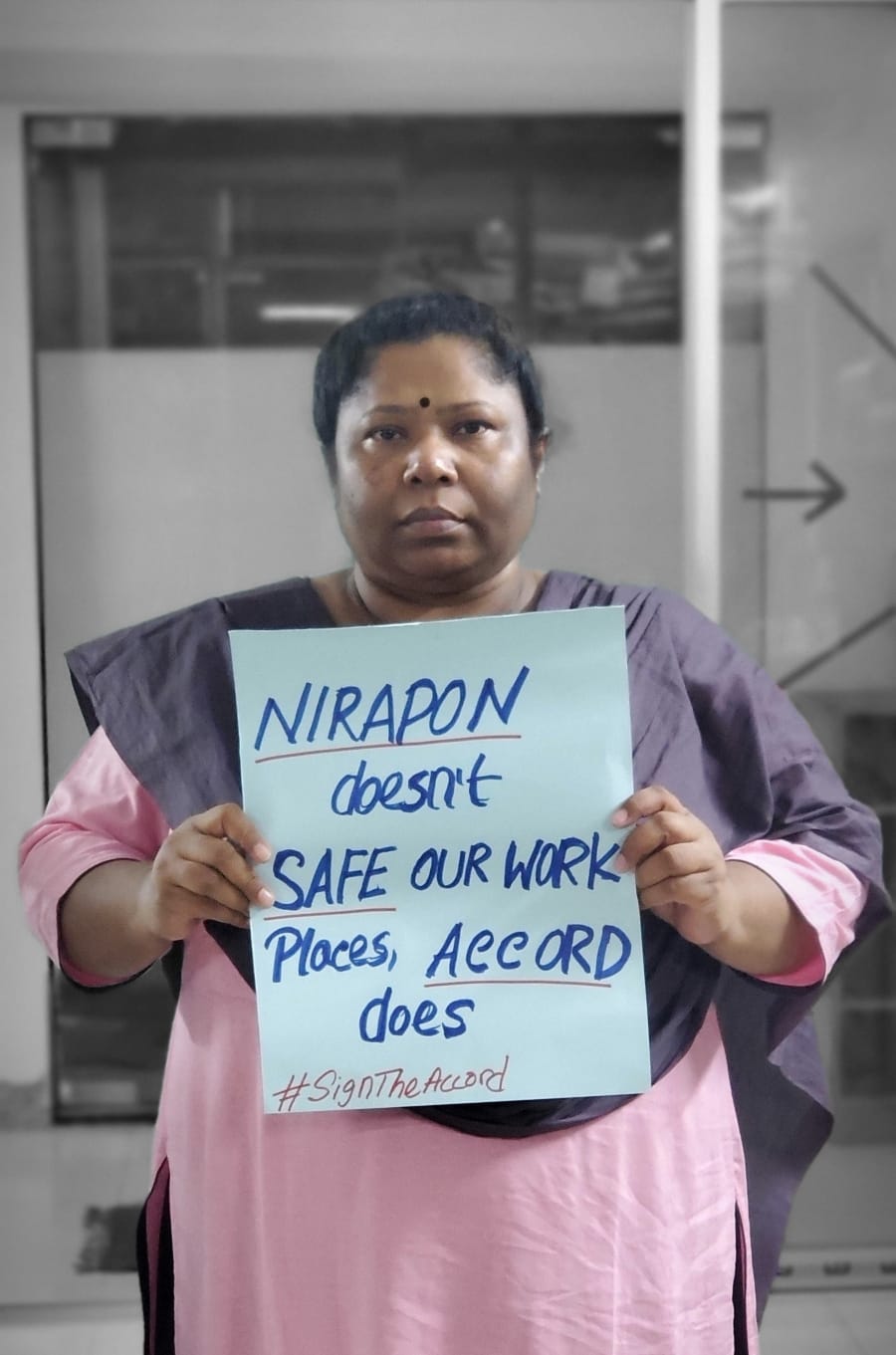

Kalpona Akter, founder of the Bangladesh Centre for Worker Solidarity and President of the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation protesting for brands to sign the Accord and stop hiding behind Nirapon.