Failing workers by design: The fatal assurances of the social auditing industry

Rasul was working in the Multifabs garment factory on 3 July 2017 when he suddenly heard a loud noise and felt something hit his head.

When he recovered in the hospital, he learned that the factory’s boiler had exploded with such force that the walls of the room were blasted out and the factory partially collapsed, killing 13 people and injuring over 50.

The Multifabs factory is not one of those hidden death traps that only work on subcontracted orders and fall under the radar of brands. The factory produced for well-known Western apparel companies and was covered by the Accord for Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh.

This binding safety programme between companies and unions however does not cover boilers. For this, the brands thus turned to the system of social auditing.

Over the past 30 years, the social auditing industry has developed into an opaque system primarily used to deflect responsibility. Auditors, working on short schedules with inadequate check lists have no incentives to look for root causes or meaningful remediation measures.

An audit report of the Multifabs factory written by TÜV Rheinland exposes these flaws. We can assess the accurateness of statements in the report, because the engineers of the Accord also repeatedly inspected the factory.

Upon completing their first inspection in April 2014, the Accord’s conclusion was crystal clear: the factory still had a lot of work to do before it could be called safe. The Accord then developed a corrective action plan for the factory, began actively overseeing remediation of the safety issues, and issued follow up reports.

The difference with the TÜV Rheinland report of May 2016 is striking. The TÜV auditor gave the factory a B score, deeming this good enough to free the factory from any follow up measures. This was worrying advise, not only because a B score still meant that considerable safety and labour rights violations were deemed acceptable, but even more so because the auditor overlooked a plethora of violations.

For example, the auditor awarded the factory an A score in the area of freedom of association and collective bargaining, despite there not being a single union in the factory.

In the field of health and safety, the TÜV auditor acknowledged that there was room for improvement. The auditor found nine safety issues in eight categories, including lack of awareness among workers about safety measures and inadequate noise protection.

Follow up was however still deemed unnecessary. The Accord inspectors came to a different conclusion. They found 131 safety violations upon their first inspection in 2014, ranging from unsafe and inadequate fire-fighting and sprinkler systems to insufficient escape routes. In August 2016, the factory had made considerable progress, but over 40 of these issues had still not been corrected.

TÜV Rheinland not only seemingly ignored many of these issues during its inspection, but even neglected to check what others had done before and never even mentions the publicly available findings of the Accord.

In response to the Mutifabs explosion, the Accord has started a pilot to include boiler safety into its programme as it was apparent that coverage by national inspection agencies and social auditing firms was insufficient. It however remains unclear whether TÜV Rheinland has incorporated these lessons-learnt into its audit design.

Sadly this case is no exception but is emblematic for how social auditing firms fail workers by design. The Rana Plaza building that collapsed in 2013, the Ali Enterprise factory that burned down in 2012, and countless factories where activists or journalists exposed forced labour, union busting, wage theft or other violations were given a stamp of approval by a social auditing firm.

Profiting from apparel companies’ need to show they care about workers, these social auditing firms have grown rich at workers’ expense - the very same workers these firms continue to profess they are working to protect.

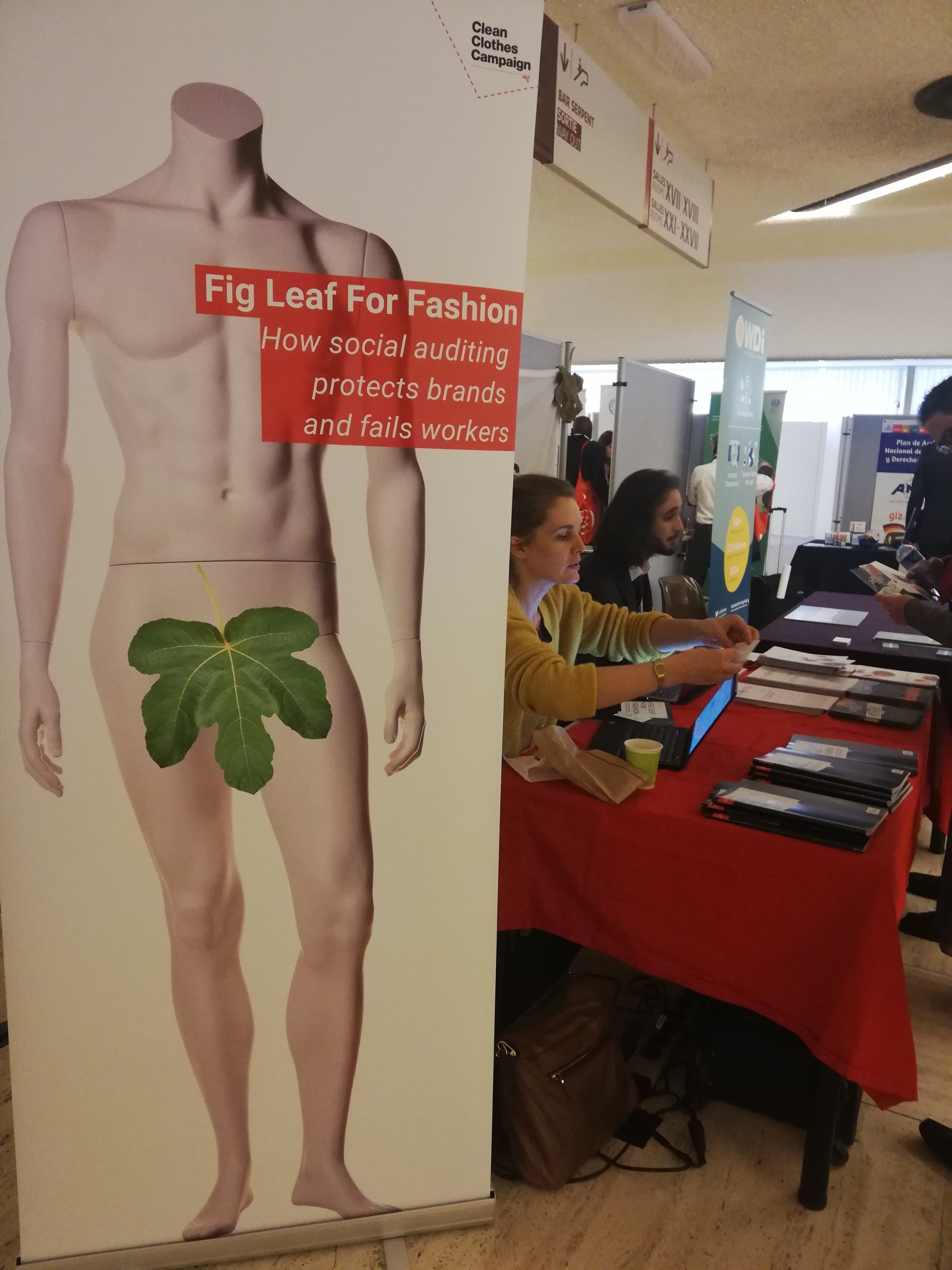

The Fig Leaf for Fashion report (and briefing summary) published by Clean Clothes Campaign in September 2019 contains a number of recommendations for what apparel companies, auditing firms, social compliance initiatives, governments, and other stakeholders must do to fix this system.

Garment workers, the majority of which are women, are experts in terms of understanding the key drivers of labour violations in the industry and therefore must be central to any long-term solutions.

At the very least this means off-site worker interviews and involvement of unions in auditing practices; a proactive approach to freedom of association and gender by skilled auditors with enough time and resources to do genuine research; publication of all audit reports to make them available to workers and activists; and the creation of functioning grievance mechanisms.

The problems in the auditing business reflect those in the garment industry as a whole and any sustainable approach should therefore address supply chain power relations and unhealthy conflicts of interest.

In the end though, the problems of the system can only be solved if all stakeholders conduct root cause analyses of the purchasing practices that keep workers trapped in a vicious cycle of abuse while perpetuating the labour rights violations that costly audit programmes unsuccessfully aim to expose and remediate.

Note: The company responses Business & Human Rights Resource Centre sought in relation to the case studies, including the one mentioned here, from the Fig Leaf for Fashion report are available here.

Authored by Christie Miedema, Clean Clothes Campaign for Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

14 November 2019