BLOG - A decade in denial

How the Sustainable Apparel Coalition is denying reality, while patting itself on the back.

The Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) may not be a household name, however it brings together many famous fashion brands in, what it describes as, the "apparel, footwear, and textile industry's leading alliance for sustainable production." Its 250+ members are said to generate a combined annual revenue of $845 billion(!) USD.

Recently, the SAC came out with a publication called 'A decade in review.' Having carefully read every page, a far better title would be: 'A decade in denial.' What could have been a good opportunity to reflect upon the serious, broad and well-founded public criticism that SAC has faced — for failing to centre workers’ rights and provide measurable transparency — has been cast aside in favour of self-serving corporate social responsibility (CSR) gibberish.

Page upon page is filled with inspirational quotes, graphics and buzz-words, every one worthy of rebuttal. The brands, in SAC's words, "come together," "celebrate milestones" and "develop bonds." In other words, they pat each other on the back and hide behind smokescreens such as 'sustainable' or 'ethical' branding, while garment workers continue to be systematically exploited for greater profits.

While touting “the bold progress … made so far” SAC fails to show any actual impact at the factory level. This is not an editorial mistake but a reflection of its real-life failure to make a difference.

If 'A decade in review' actually mirrored reality, it would show workers being paid poverty wages yet still having billions of dollars in wages stolen from them; working excessive (frequently forced and/or unpaid) overtime; experiencing gender-based violence, abuse and intimidation on the factory floor, and suffering many other human rights violations, all of which 'A decade in review' fails to acknowledge.

That SAC's focus is on protecting brand reputation rather than protecting garment workers' rights is obvious. It has long been known that the whole practice of social auditing is fatally flawed, yet nevertheless SAC persisted and between 2018 and 2020 it developed yet another scoring methodology, the 'Facility Social & Labor Module' (FSLM). This will do nothing to remedy the urgent and very real violations garment workers face daily.

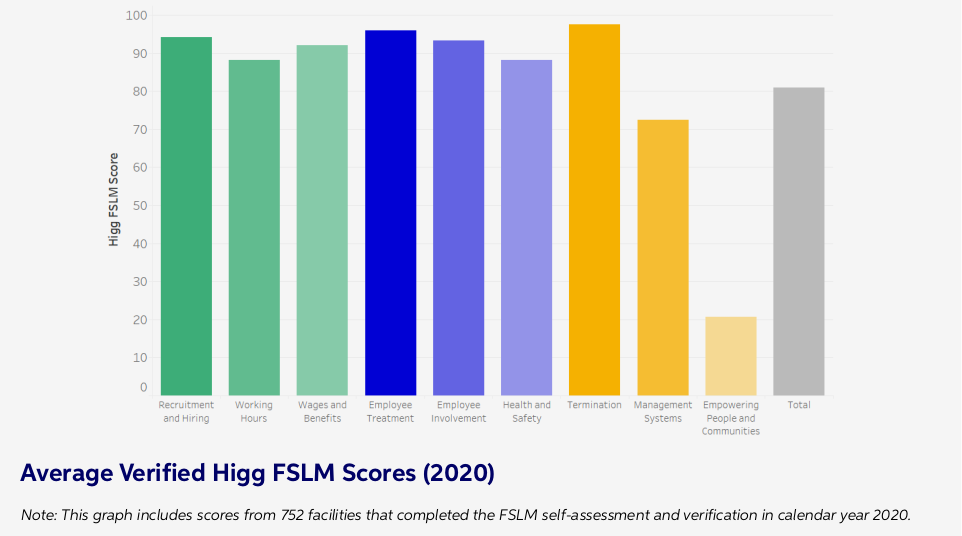

In a cheerful graphic on page 30, we discover that in 2020, over 750 factories have scored in the 90% range for 'Wages and Benefits,' 'Working Hours,' 'Employee Treatment' and 'Termination.' There are no words for how out of touch with reality this is; 2020 was the year the pandemic hit and the reaction by brands - many proud members of SAC – caused hunger, wage theft and labour rights violations on a massive scale. These scores represent a complete disconnect with garment workers' realities.

Among many other problematic aspects, 'A decade in review' displays utter disregard for workers’ freedom of association. This is a core enabling right that supports upholding other human rights, but it has been under sustained attack in the garment industry. Every day workers are being prevented from forming and/or joining trade unions in the value chains of SAC’s member brands, and SAC has done virtually nothing to change that.

In SAC’s long membership list there are many brands that have been the focus of our public campaigns over the past decade, as well as of behind-the-scenes assistance to the workers whose rights have been violated while they were or still are producing those brands’ clothing.

One example (of many) are Boohoo workers in the UK, where CCC UK/Labour Behind the Label has been campaigning on their behalf. Workers in Leicester are owed millions of pounds in back pay after years of £3.50/hr work, well below the minimum wage, which has established itself as a norm. This illegal exploitation has led to mass profits for Boohoo, who used cheap manufacturing costs to build their business into a multi-million-pound profit engine. Despite media exposés on poor factory conditions, Boohoo's profits have soared during the pandemic, rising by 51% in the first half of 2020 alone, with Boohoo making £68.1 million in profits in the six months to 31st August.

If 'A decade in review' was not actually 'A decade in denial,' it would also have to talk about H&M’s broken promise that 850,000 textile workers in their supply chain would be paid a living wage by 2018. Our research revealed that in 2018, workers producing for H&M in Cambodia earned less than half of the estimated living wage, and workers in India and Turkey were paid approximately one-third of a living wage. In Bulgaria, workers interviewed at H&M’s “gold supplier” earned less than 10% of what would be required for workers and their families to live decent lives.

There is only one page (33) in the entire report that contains actual results on environmental impact, but even these are minimal. Of the facilities that completed their flagship environmental module over the past three years, a whopping "less than 5% completed verification". And that only addresses the environmental impact of factories; the devastating effects that producing ever-more fast fashion has on the planet and its contribution to the climate crisis are carefully kept out of focus.

SAC tries to cover up their lack of actual impact with an ‘ecosystem’: an ever-growing web of equally pointless organisations developing "deep relations" in agreement with one another. Effectively, it is SAC agreeing with itself. Spinning up the Higg Index, the Apparel Impact Institute, the Social & Labor Convergence Program, the Policy Hub and more, and then “creating connections” at various conferences seems to be the only real impact of the past 10 years. While that must have contributed to the hospitality and airline industries, it has yet to improve garment workers' lives.

SAC’s flagship Higg Index is touted as a “game changer”, but the rules of the game remain the same:

- Brands dictate low prices, short deadlines, unstable orders.

- Workers pay the human cost.

All in all, 'A decade in review' begs the question: What is the point of a methodology that delivers no results?! Sure, CSR sounds nice to consumers and lots of people get cushy white-collar jobs, but factory workers and their families still live in deprivation.

To add insult to injury, the review lays out a new “strategic plan” with lofty goals, namely that “SAC enables and supports workers’ rights, safety, and livelihoods by 2025.”

Really?

If that had been a goal in 2010, it would have been more than fashionably late. At this point it is nothing if not quite telling of SAC’s lack of actual impact so far and of their continued disregard for garment workers’ urgent needs.

If SAC wants to show itself as relevant, the only way forward is to replace meaningless CSR smokescreens with concrete action. That would mean SAC members immediately sharing a much larger part of that $845 billion pie with the women and men whose labour powers the industry and on whose backs those profits were made. Only then will SAC produce a report worth reading.

Neva Nahtigal & Paul Roeland